Why top clubs might be culling their old players too soon

Bastian Schweinsteiger, Stewart Downing and Steven Gerrard have all been dispensed with this summer thanks to ageing bodies, but Alex Hess says some clubs are jumping the gun...

On the face of it, the transfers of Bastian Schweinsteiger and Stewart Downing a fortnight ago had little in common beyond simple temporal proximity. Both involved a hometown club: the German bid farewell to his after a decade-and-a-half of diligent service, with Downing playing the role of prodigal son six years after his own departure from the north-east.

Other than this, though, you’d be hard pressed to spot any real parallels. And yet, there is something else that unites them, something significant. To varying degrees, both illustrate a trend that seems increasingly prevalent within today’s transfer market: a creeping mistrust of ageing players.

Of course, age alone wasn't the reason for any of those moves. And yet it was most certainly a factor in each of them. Schweinsteiger, a World Cup winner only a year ago and just about as high pedigree a midfielder as you’ll find, was allowed to leave Bayern Munich by a management who, by all accounts, sensed – or at the very least feared – deterioration not far around the corner. He will be 31 when the new season starts.

2014/15 20

2013/14 23

2012/13 28

2011/12 22

2010/11 32

Downing was earmarked for the exit door pretty much immediately after Slaven Bilic’s appointment at West Ham, made to train alone as a result. The Teessider also turns 31 this week and, given that last season saw him produce his best form for many a year, it’s hard to see that fact as anything other than central to Bilic’s ruthlessness.

Over in Turin, there were no trees torn up by Juventus when Carlos Tevez – another returning hero, another 31-year-old – announced his desire to return home to Boca Juniors. It is impossible to know how much heed was paid in the Juve boardroom to the fact that the Argentine had amassed 50 goals over his two years in Italy, helped the club to four trophies in the process, and was showing little if no sign of slowing anytime soon. But it’s fair to say that any struggle to retain his services was minimal.

Thirtyphobia

It is impossible to quantify, but certainly it feels as though these days – with transfer and contract negotiations now generating as much coverage as the football itself, and with players as much athletes as they are technicians – far more weight has become attached to age. The result? Call it thirtyphobia. The unspoken, sport-wide supposition that the moment a player exits his twenties is the moment to start engineering his departure. That 30 is the beginning of the end.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

And it may largely be true, of course. But as with all tendencies, there are exceptions.

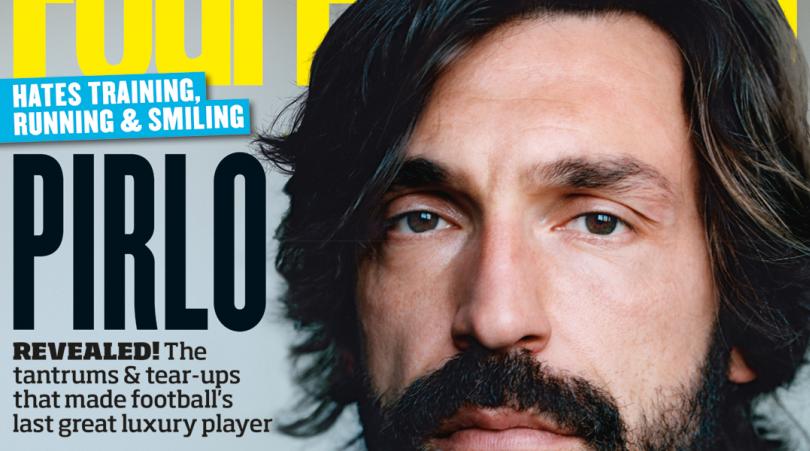

It was in Turin where the starkest and most widely cited exception occurred. Back in summer 2011, five days after his 32nd birthday, Andrea Pirlo completed his move to Juventus from Milan, who had decided the time was right to send the bearded puppeteer on his merry way.

Four years, four straight league titles and one self-styled cult hero later, it’s fair to say that Pirlo has fully demonstrated how mileage and decline don't always work in perfect tandem. (And there’s no small irony in the identity of the selling club in that instance, given how the mythical Milan Lab has become famed for the exact opposite: extracting value from age by adding a precious few years to the career of many a weathered superstar.)

In a similar vein – and, by no coincidence, at the same age – Xabi Alonso was ushered out the Real Madrid exit door last summer when it became apparent that the younger, spritelier Toni Kroos was keen on a move to the Spanish capital. Alonso, spotting a ready-made and poignantly Kroos-shaped vacancy in Bayern Munich’s midfield, made the reverse journey and quickly went about demonstrating that being 32 doesn’t preclude a capacity for elite-level football.

He became Bayern’s pivotal midfielder with near-immediate effect, finished his season with a league winners' medal, and could be forgiven for indulging in a spot of schadenfreude when Real Madrid ended theirs trophyless.

All in the timing

Of course, in and of itself, the footballing Indian summer is anything but new phenomenon. That a ticking clock can bequeath inordinate value has long been known to clubs seeking out the transfer market’s loopholes, with Gary McAllister, Teddy Sheringham and Luca Toni just three of the modern era’s more celebrated examples.

At 36, Johan Cruyff made use of his final season as a player by defecting from Ajax to Feyenoord and helping his new employers to the Dutch double. Further back still, Stanley Matthews finished his career by returning to hometown club Stoke, presenting them with promotion to the top flight and pocketing the Football Writers’ Association player of the year award in the process. His age? 48.

On the flipside, there’s an equally fine art to selling a player at the moment when value and output are at their peak. For years it was Arsene Wenger who was the grand master of this, ensuring that the likes of Marc Overmars, Patrick Vieira and Thierry Henry bestowed Arsenal both their finest footballing years and a handsome sum at the end of them.

These days, it’s Chelsea who seem to have perfected the art of the well-timed, well-remunerating sale. Clubs have always had to tread carefully when a player hits thieir late-twenties, but one senses that the cold feet are beginning to come earlier.

Because the emergence of thirtyphobia has been a gradual sea change rather than a sudden lurch, it's difficult to identify any milestone events. But perhaps the acquisition of Dimitar Berbatov by Manchester United is the closest thing to one that exists.

Berbatov was 27 when United broke their own transfer record to recruit him for £30.75m. That is hardly ancient, of course, but while the Bulgarian was perfectly decent on the pitch during his four seasons at United, he represented rather meagre value for money off it, eventually sloping off to Fulham in 2012 with just £5m recouped into the Glazers' coffers.

It's no accident that, with one notable exception (more on him shortly), in the seven years between Berbatov’s arrival in 2008 and Schweinsteiger’s last week, United had not paid a single cent in transfer fees for an outfield player over the age of 26.

Rocking Robin

The notion of age-related caution precedes Berbatov, but the effects of that episode in hardening doubt into dogma may have extended beyond Old Trafford. Its legacy certainly told in United’s overhauled transfer policy, but perhaps also in Chelsea's strikingly parsimonious new contract policy, in the sales of Rafa van der Vaart from Spurs, Nigel de Jong and Gareth Barry from Manchester City, and in the mass exodus of Craig Bellamy, Dirk Kuyt and Maxi Rodriguez from Liverpool, all in the summers of 2012 and 2013.

All of those players had contributed sturdily immediately before being sold, and all their clubs missed them once they'd left.

If there's a message to be taken, it’s that having an overriding strategy of replenishment is all well and good, but the above sales – especially at Anfield – show the folly of fundamentalism. It would be no shock if the exits of Schweinsteiger, Downing or Tevez were looked back on as similarly premature next May. Experience often has a value that runs beyond mere pounds and pence.

Which brings us to that notable exception, Robin van Persie. His transfer to Old Trafford in summer 2012 (fee: £24m, age: 29) perfectly demonstrated both the perks and the perils of gambling on an elder statesman.

In his first year the Dutchman was the proverbial force of nature, his 26 league goals and Cantona-esque powers of infectious renewal helping United recapture the league title from their local rivals, and in Alex Ferguson’s farewell season no less.

Whether United would have claimed that trophy without Van Persie is deeply doubtful. But a steep downturn in form and fitness thereafter saw him, due to age, wage and club politics, acting as much a hindrance to United as a help for long stretches preceding his eventual move to Fenerbahce.

A cynic would speculate that yes, perhaps Old Trafford’s bean counters did go on to regret signing Van Persie. After all, whether the club’s windfall from their 2013 title was enough to offset the outlays in transfer fees and wages is unlikely. But then again, there are many long-term merits (including financial ones) to the more intangible concepts – hunger, glory, eminence – which Van Persie’s arrival helped restore at United.

Ask any Stretford End regular if the signing was a good one and the answer is likely to be the same. It will be little surprise if it’s a similar story for Schweinsteiger in three years’ time.

Funnily enough, given that they’re among the strictest proponents of transfer market thirtyphobia, it's United who have best demonstrated that, amid all the talk of resale value, contract lengths and diminishing returns, there’s quite often one truth which trumps all others: sometimes it’s best to just have the player, and worry about the rest later.