World Cup icons: Zinedine Zidane heads France to victory – but doesn't change society (1998)

Ahead of FFT's France 98 World Cup Final watchalong this Saturday, we remember Zinedine Zidane's extraordinary contributions in that tournament, and French society's reaction to the victory

Late on the evening of July 12, 1998, one million people poured onto the Champs-Elysees in Paris. The world’s most famous avenue was a flurry of tricolore flags, the sound of car horns and cheers of fans filling the night sky.

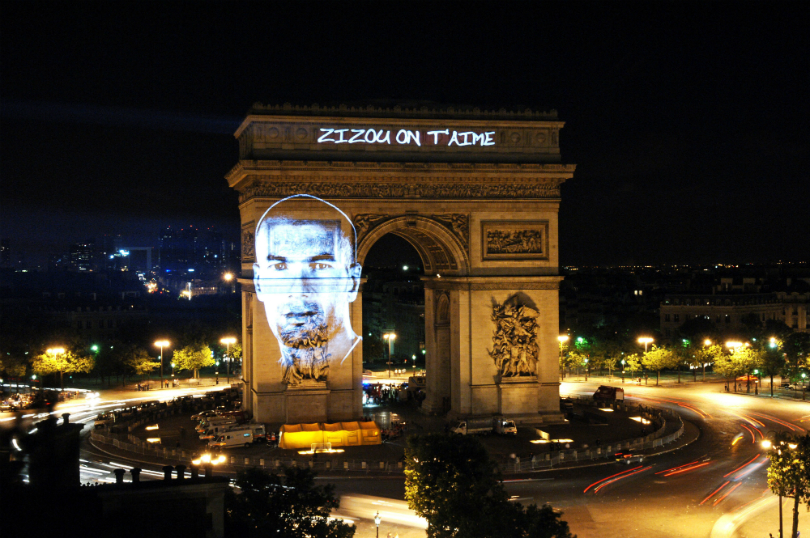

As the throngs partied, an image of Zinedine Zidane was projected onto the Arc de Triomphe along with two words: ‘Merci Zizou’. The masses roared in appreciation and, in that moment, Zidane’s status as the foremost cultural icon of his generation in France was sealed.

A couple of hours earlier, the 26-year-old Juventus playmaker had scored two headers in the 3-0 win over Brazil which meant that France were crowned world champions for the first time. He’d had a mixed tournament, and not even been France’s best player – that was Lilian Thuram – yet those two goals in the final meant he emerged as the post-tournament face of the team.

Use of his image was about a lot more than football. It was about cultural identity, race, ethnicity and immigration – all massive talking points in host nation France before, during and after the finals.

During Euro '96, far-right National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen had sparked outrage when he criticised the multiracial nature of the squad, describing France as a team of foreigners. To anybody with even a passing knowledge of Les Bleus’ history, his comments were ignorant and bizarre.

‘Black, Blanc, Beur’

The best-known members of the France team who reached the 1958 World Cup semi-finals were Raymond Kopa, the son of Polish immigrants, and 13-goal tournament top scorer Just Fontaine, born in Marrakech to a Spanish mother. 1980s legend Michel Platini had an Italian father. Defender Marius Tresor was born in Guadeloupe. Midfield lieutenants Jean Tigana and Luis Fernandez were born in Mali and Spain respectively.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Le Pen was a powerful figure who had turned the National Front from a fringe party into a major political force. His remarks threw open a debate about what it meant to be French at the end of the 20th century. The ’98 squad included several players born outside metropolitan France (Bernard Lama, Christian Karembeu); others, such as Zidane, Youri Djorkaeff and Marcel Desailly, were children of a parent or parents who’d emigrated to France.

The team were known as ‘Black, Blanc, Beur’ (Black, White, Arab) – a wordplay on the red, white and blue colours of the French flag – and victory was seen as the perfect riposte to Le Pen.

At the centre of it all was Zidane, not only a fantastic footballer but a hugely popular figure. Several times in subsequent years he was voted France’s best-loved personality. As the star player, and a boy born into a working-class family in Marseille to parents who had moved to southern France from Algeria, he came to stand for everything that Le Pen opposed.

On wider matters, however, Zidane had virtually nothing to say. He sidestepped questions about identity and immigration as deftly as he did ill-timed tackles from off-balance defenders. The old adage about letting his football do the talking had never been more apt. He wasn’t so much a reluctant figurehead as a silent one.

Cynics argue that there was something calculating about Zizou keeping his counsel: by being disengaged with more important topics, Zidane was then able to cash in on the many advertising opportunities that came his way. In a similar manner to future Real Madrid team-mate David Beckham in England, Zidane was the one player whom brands clamoured to be associated with; a blank canvas who was capable of enhancing any product.

Silent suspicions

And yet perhaps there was a simpler truth behind Zidane choosing to hold his tongue. He seemed to realise from the outset that he was just a football player, and that lending his voice to broader issues was fraught with danger. He also appeared to grasp that the supposedly positive impact of the 1998 World Cup-winning side on French society as a whole would be fleeting or even illusory.

Whatever hesitations Zidane may have had proved well-founded. For several years there was talk of the country unifying around the ‘Black, Blanc, Beur’ generation, but life carried on as normal.

In 2011, then-France manager Laurent Blanc was caught up in scandal when he was secretly taped criticising dual-nationality players who opted to represent countries other than France. In 2017, Le Pen’s estranged daughter Marine outstripped her dad’s achievements when she took 34 per cent of votes in the final round of the presidential election.

For the French, Zidane and 1998 will always be about much more than football. Twenty years on, however, that period has taught us that football may reflect society, but cannot change society quite as much as we would like.

World Cup Wonderland: stories, interviews and more

NOW READ…

QUIZ Can you name all 98 teams in Europe's top five leagues?

GUIDE Premier League live stream best VPN: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world

James Eastham is a specialist writer covering French football. He has written for The Guardian, The Independent and When Saturday Comes magazine. He’s interviewed many leading figures in the French game, including Didier Deschamps and Kylian Mbappe. For a decade he also worked as a freelance football scout, covering games at all levels from U16 to the senior national team across France