The worst five months in English football: Thatcher, fighting and fatalities in 1985

If 1984 was a bad year for England, then 1985 was utterly disastrous – not least if you were a football fan. Richard Edwards remembers Maggie's meddling, an appalling May and the start of the supporter strikeback...

The Thatcher administration had spent 1984 battling the miners and dismantling the coal industry. But with that fight almost won, by the time the clock had ticked lazily into the New Year, she had another of the country’s best-loved and most established institutions squarely in her sights – English football.

History has shown that the first five months of 1985 were among the most miserable ever experienced in the national game. But from the low points of the Luton Town riot, the Valley Parade fire and the Heysel disaster, football managed to start the long process of reinventing itself.

Two Britains emerged in the 1980s. The rich got richer but the bottom 10% saw their incomes fall by about 17%"

However, the very notion of football having a future came into question. The establishment saw football as nothing but trouble and the beautiful game was about to realise its unpopularity among the country's decision-makers.

“Two Britains emerged in the 1980s,” writes Andrew Marr in his History of Modern Britain. “The rich got richer but the bottom 10% saw their incomes fall by about 17%. A lot of people fell through the cracks. Once Britain had prided itself on not seeing people sleeping on the streets or begging. Not any more.”

Football itself was entering begging bowl territory. By the end of the 1983/84 season, the average attendance in England's top flight had fallen to a paltry 18,834 – a disturbing drop of almost 8,000 since the turn of the decade. Aston Villa – European Cup winners just two years before – were now welcoming just 21,371 through the Villa Park gates. Wolves, meanwhile, could only muster average crowds of 12,478 at a ramshackle Molineux.

And as crowds dwindled, the column inches devoted to events off the pitch increased exponentially as unemployment levels reached 12% by January 1985 in a country more divided than at perhaps any time in its history.

You were weeing against a tin wall with a trench dug into the ground"

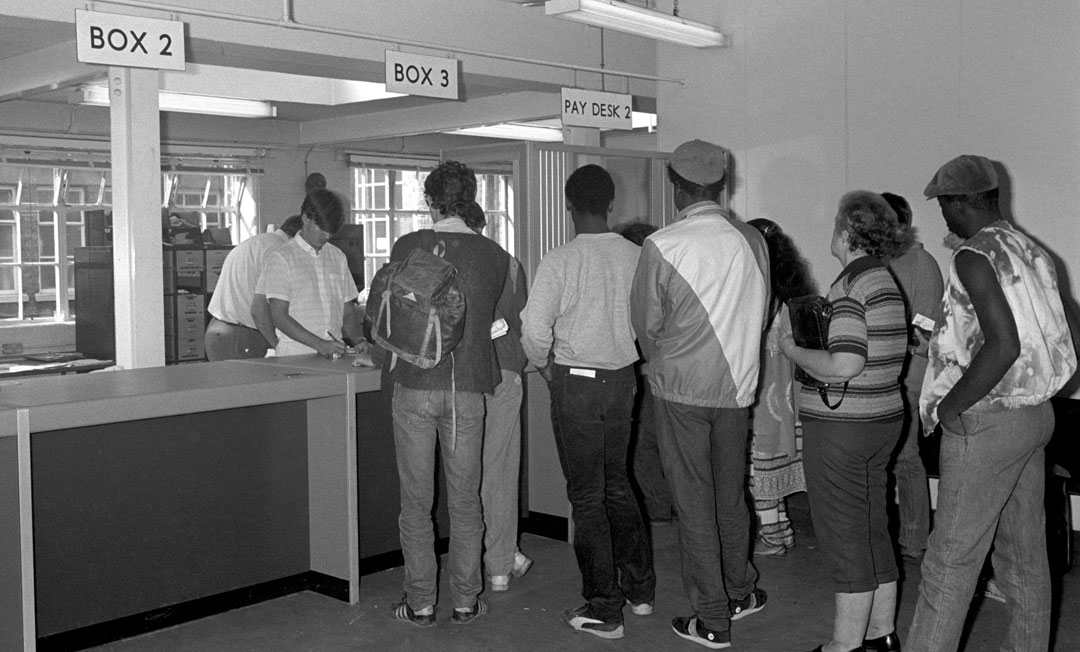

Lower down the leagues, fans were forced to put up with conditions more akin to the 1880s than the 1980s.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“We were all tarred with the same brush by the authorities,” says Paul Davison, a Bradford City fan who was at Valley Parade for the Bantams' promotion party against Lincoln City in May of that year.

“There was no money in football and as an away supporter you got even worse treatment than home fans. You would stand on crumbling terraces, all the toilets were outside and you were weeing against a tin wall with a trench dug into the ground.”

Hoolies let loose

Distracted by her battle with the miners she may have been, but Thatcher still took the view that football hooliganism represented the very worst of the nation’s ills. By the time the final whistle had blown on a tumultuous and ultimately tragic season in May 1985, the Iron Lady – two months on from watching the defeated miners trudge back to work – was eyeing up significant changes in the British game.

“The government held the view that something had to be done,” says Peter Garrett, a co-founder of the Football Supporters Federation (FSF) – established 30 years ago this summer. “And it was the ordinary fan who was going to get trampled on. Some of the ideas were ridiculous, they were never going to work: there were so many schemes, so many ideas and they simply weren’t practical.

“Yes, there were hooligans and yes, there was the taunting and baiting, but a lot of it was ritualistic rather than threatening. If you were an ordinary fan going to a game then you were unlucky if you found trouble. A lot of it was mythology.”

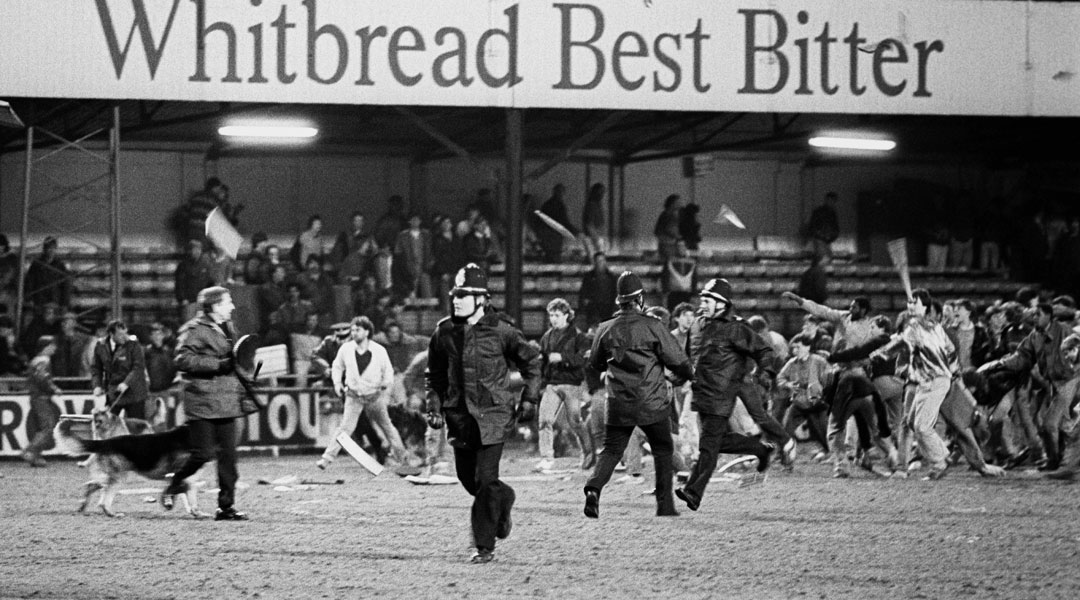

The very real events at Kenilworth Road on a drab Wednesday evening in March did, though, simply harden Thatcher’s resolve to impinge the civil liberties of those who chose to follow it.

We became pariahs. [The chairman] was Mrs Thatcher’s plaything. He wanted a safe Tory seat"

Inexplicably, the FA Cup quarter-final between Luton and Millwall wasn’t an all-ticket affair, which gave Lions’ supporters carte-blanche to rope in some ‘help’ from fans of Chelsea and West Ham in a rampage that further stained the already far-from-spotless reputation of English fans both domestically and, crucially, in Europe.

For Luton chairman David Evans, a close confidant of Thatcher, the behaviour of those travelling up from London proved to be a surprising blessing in disguise. His club’s ground had been trashed but it offered him the perfect opportunity to cosy up to the Prime Minister and win her favour by mooting the idea of banning away supporters from grounds and introducing ID cards.

“We became pariahs,” David Pleat, Luton manager at the time, told The Guardian on the 30th anniversary of the clash. “He was a naughty boy, David. He was Mrs Thatcher’s plaything. He wanted a safe Tory seat. I didn’t agree with it but there was no discussion, no debate.”

That was just the way Thatcher wanted it (and unlike visiting supporters, Evans got his seat, being elected in 1987 as MP for Welwyn Hatfield). By the Friday of the same week, Brentford had cancelled their weekend match against Millwall over safety fears and Home Secretary Leon Brittan was threatening to introduce life imprisonment for those found guilty of serious hooliganism-related activity.

Football riots are nothing less than outbursts of savagery; they threaten the future of football and they smear the country’s good name abroad"

“Football riots are nothing less than outbursts of savagery; they threaten the future of football and they smear the country’s good name abroad,” he said.

On April Fools’ Day, Thatcher – presumably not in the mood for hoaxes – met with officials from the Football Association and Football League and unveiled a six-point plan that included the introduction of ID cards, better fencing and closed-circuit television. They weren’t so much a set of proposals as a list of demands for football clubs who, she deemed, weren’t doing enough to tackle the problem.

They had six weeks to get their houses in order, but no one sitting around that Downing Street table could have envisaged the perfect storm that was about to be unleashed.

Maggie's May

On May 11, football was plunged deeper into misery by a disaster rooted more in long-term negligence than terrace hooliganism. In the final game at Bradford's Valley Parade before a long-planned rebuilding of the main stand, fire caused the death of 56 fans who had done nothing more than turn up to watch their team celebrate a first promotion in half a century. It was the worst tragedy suffered by British football since 66 supporters had died at Ibrox in 1971. It left a country in shock and a city bereft as it counted its dead.

On the same day at St Andrew's, a wall collapsed as Birmingham fans clashed with Leeds supporters, causing the death of 15-year-old Ian Hambridge. He was attending his first professional football match with his dad, who reportedly hadn’t been to a game for four years because of fears over crowd violence.

Then came Heysel.

Ignoring the preposterous decision to hold the European Cup final at a crumbling ground that was hopelessly ill-equipped for a game of that magnitude, the Prime Minister wasted no time in pinning the blame on Liverpool’s supporters.

Thatcher spoke almost immediately of withdrawing English clubs from European competition, her fire fuelled by rumours that the Heysel trouble was orchestrated by left-wing agencies across the continent.

“The facts are as yet imprecise, but there is grounding for belief that the quite clearly organised assault by alleged Liverpool supporters in the Heysel Stadium had financial and ideological backing from left-wing agencies outside Britain,” wrote David Miller in The Times.

With that kind of paranoia permeating the corridors of power in Whitehall, it’s little wonder that a new battle was kicking off between the government and football fans. With pitifully little resistance – the Conservatives had almost twice as many MPs as a Labour party struggling to fight off the new Liberal/SDP Alliance – Thatcher sensed an opportunity to put the sport well and truly in its place, eventually announcing legislation demanding football fans be made to carry ID cards.

“She hadn’t been briefed by anyone who knew what was going on and what had happened at Heysel,” says Garrett. “Graham Kelly [then the secretary of the Football League] was incensed at the suggestion that English clubs should be banned from European competition, because he knew what was going to happen.

“If they were banned for any particular length of time, then to try to re-establish themselves would take forever. It was catastrophic, and although the Premier League has in some ways made up for it, we’ve never had the sustained success in the Champions League that we had in the European Cup.”

Fans fight back

It was out of this disillusion that the FSF was formed. Aimed at providing a platform for downtrodden fans to not just voice their opinion but also oppose and highlight their treatment by an administration seemingly determined to hold them up as a cause of the country’s ills, the idea immediately caught the public’s imagination.

Heysel gave birth to the Premier League. Another organisation born out of a tragedy"

The body also handed Thatcher the opposition that was so sadly lacking in Westminster, although it was already too late to do anything about the self-imposed ban on English clubs performing in European competition – one quickly ratified by UEFA and kept in place until 1990, prompting the game's biggest clubs to get together and start discussions over a breakaway league. As Rogan Taylor, the FSF's first chair, wrote later: "It was Heysel that gave birth to the Premier League. Another organisation born out of a tragedy."

Although the Prime Minister would have been delighted to know that football's future involved not just a significant reduction of hooliganism but also an enormously profitable organisation using market forces to export British-based businesses to a worldwide audience, none of this was known when she stood on the doorstep of 10 Downing Street just two days after the disaster.

“We have to get the game cleaned up from this hooliganism at home," she said, "and then perhaps we shall be able to go overseas again.”

In just 16 May days, 96 fans had lost their lives watching the sport that they loved, leaving English football at an all-time low.

Worse was to follow, but by the time the 1985/86 season began, the fan fightback had started. The miners may have been defeated but Thatcher was about to find football an even tougher nut to crack.

IN THE NEW ISSUE The untold story of the Taylor Report