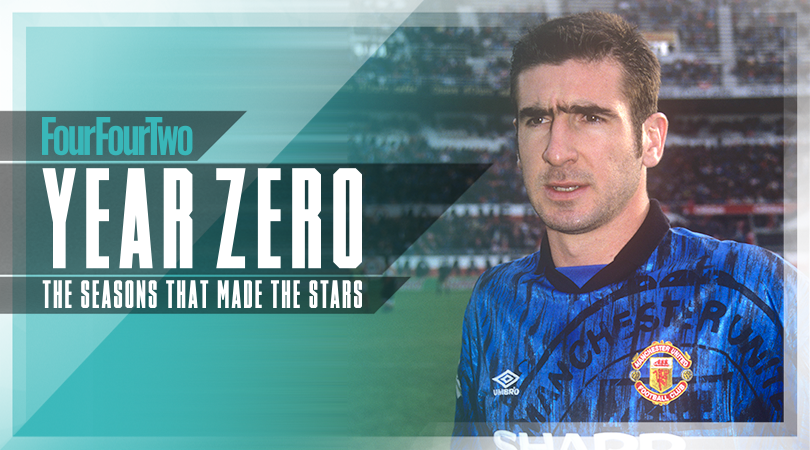

Year Zero: The making of Eric Cantona (Leeds/Manchester United, 1992/93)

Hounded out of France as a troublemaker, distrusted by his manager at Leeds, the 26-year-old Cantona signed for Manchester United for £1.2m – and became a legend

On a murky Mancunian afternoon, just under a month out from Christmas 1992, a mustachioed Manchester United fan stands in front of a Megastore Santa and reacts to the news that his club, lying eighth in the Premier League and out of both the cups, have just signed a French forward from Leeds. “Ooh aah Cantona?” he mutters, shaking his head. “They won’t sing it here.”

This feature was originally published for our Year Zero series, and is republished here for Cantona week

While others might have been a little more optimistic about the new arrival, the talking head’s opinion was by no means unreflective. Gary Pallister was told the news by a journalist, who first made him guess who his boss had just splashed out for (“I was stunned”).

Lee Sharpe didn’t believe it either. “Yeah right, absolutely no chance,” was his first reaction. “The bloke’s a total nutter.” And across the nation, bemused supporters looked upon the Teletext page 302 headline: “OOH AAH, I’VE GOT CANTONA” with a mixture of scepticism, glee and confusion.

Cantona’s talent, of course, was not in doubt. This was a France international of prodigious ability, who had played a delicious cameo in Leeds’ burglary of the title from United the season before. But his reputation as a troublemaker was ominous. Howard Wilkinson didn’t like the Frenchman’s attitude and thought he was idle, despite the goals he was banging in.

Rewind further, and the story of a player unable to settle pretty much anywhere unfolded.

7 DAYS OF KING ERIC Cantona week on FourFourTwo

Sure, he’d started well at Auxerre under Guy Roux, but Cantona had laboured at hometown club Marseille, ending up on loan to Bordeaux and Montpellier. There were reckless tackles. Shirts and fists were thrown. He’d insulted national coach Henri Michel on live TV, and thrown boots into the face of Montpellier team-mate Jean Claude Lemoult.

At Nimes, though, he’d got into real trouble. Banned for a month after tossing a ball at a referee, he later walked up to each member of his disciplinary committee and called them an idiot. His suspension was doubled. Just 25, he decided to retire.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Then, France assistant manager Gerard Houllier – and Cantona’s psychoanalyst – had persuaded him to try a fresh start in England. So far, it had worked out perfectly. But as Bryan Robson recalls from the time, United was a different proposition. “The players weren’t convinced that it was a good signing. Eric had a reputation for flitting from club to club.”

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves: Eric Cantona’s 1992/93 had started at Leeds United – and started extremely well. He was playing for the champions, and was already idolised on the Elland Road terraces. Despite having only played a bit-part role in their dramatic title surge, the early signs were that he could become a club great.

He’d hit an incisive hat-trick in the Charity Shield – the 4-3 against Liverpool – and went on to notch 11 times in his first 20 games (including another treble vs Spurs and two in the Champions League).

The only problem was that Wilkinson didn’t fancy him. “He’s got exceptional potential, but he’s got to keep hard at it,” he muttered about his match-winner after the dazzling Charity Shield display. Eric lacked the consistency he’d later show in Manchester, perhaps because he didn’t sit comfortably inside Sergeant Wilko’s strict 4-4-2.

ALSO READ Why did Leeds sell Eric Cantona to Manchester United?

His languid style rubbed the gaffer up the wrong way. “I had a bad relationship with Wilkinson,” Cantona would later tell FourFourTwo. “We didn’t have the same views on football.” Likewise, Cantona baulked at the endless fitness drills in training.

But there was no doubt that his four-month spell at the beginning of this term displayed an individual ready to soar. In a parallel universe, with a more accommodating boss, Cantona might have helped to kickstart an entirely different dynasty on the other side of the Pennines.

Rumours, meanwhile, swirled about what Cantona was up to off the pitch. True or not, he was unsettled, and the now-famous phone call between United chairman Martin Edwards and his Leeds counterpart Bill Fotherby would seal his switch. The Yorkshireman wanted to sign Denis Irwin: there was no deal to be had, but Ferguson signalled to his boss that he’d be interested in Eric.

To their surprise, Fotherby said it was a possibility. After some back and forth, a fee between £1m and £1.2m was settled upon. When Ferguson told his assistant, Brian Kidd, the Mancunian enquired whether Cantona had lost a leg.

The immediacy and depth of Eric’s impact shouldn't be overstated – it’s worth remembering the state United were in. Yes, they were the best-supported club in England, but given this fact, United had horribly underachieved overall.

Pre-Eric, they’d won just seven titles in 114 years. It wasn’t good enough for a club of their size and buying power. And the capitulation to Leeds had sent the fans into something resembling mourning. They’d blown the title from a strong position, and some loyalists felt that the club was somehow cursed, destined to never break the title hoodoo that now extended into a 26th season.

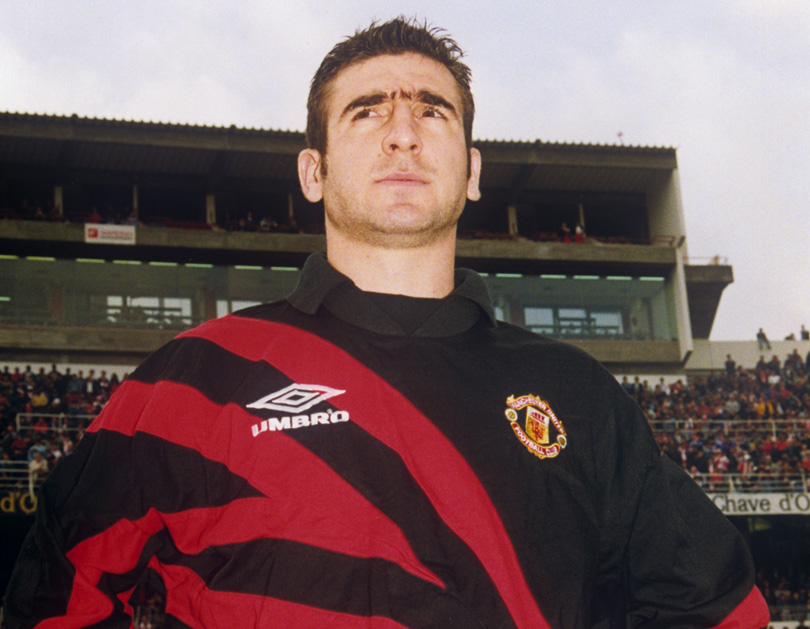

What Cantona brought, above all else, was confidence. “He swaggered in,” remembers Ferguson. “He stuck his chest out, raised his head and surveyed everything as though he were asking: ‘I’m Cantona. How big are you?”

United had a world-class goalkeeper in Peter Schmeichel, the league’s meanest defence – marshalled by the sturdy Steve Bruce and Gary Pallister – and plenty of fight and bite in midfield. But they lacked someone to help get them over the line when it really counted; someone lacking the fear that had gripped the club as they’d let the league slip. Someone with infallible belief and an X-Factor.

Cantona filled the void. “He just had that aura and presence,” Paul Ince recalls. “He took responsibility away from us. It was like he said: ‘I’m Eric, and I’m here to win the title for you.’”

On the training ground, youngsters like Ryan Giggs and Gary Neville idolised him. The well-worn cliche of the pro who stays late after training to practice was true in Cantona’s case, and it inspired others to reach for his level of excellence. “He would come in at half past nine in the morning, an hour before us lot, do his own warm-up and practise his skills and his touches,” says Ince.

The ball-hurling madman of myth was nowhere to be seen, either. “He was nothing like the guy we feared he’d be,” said Mark Hughes. “He was polite and considered, and drove a modest car and lived in a modest house,” said Gary Neville. He raised standards just by being Cantona.

“Even the slightest mishit, or a lost tackle, would earn you a glare,” adds Neville. “You'd feel two inches tall. A mistake was a crime in that team.”

United’s form had an immediately uptick. Eric helped grab crucial draws at Chelsea and Sheffield Wednesday, then scored as the Reds dismantled Coventry City and Spurs. A month after his arrival, United were top of the league. Cantona brimmed with a regal confidence and imagination on the ball, and saw the game like nobody else.

Visionary passes would release the likes of Giggs, Irwin and Andrei Kanchelskis on the flanks. He supplied Hughes with glorious chances (the Welshman scored 15 that year). And when the team struggled and needed something special he was there to grab games by the scruff of the neck: he scored a late winner against Sheffield United, salvaged a desperate draw in the March derby against Manchester City, and netted nerve-calming third goals in the run-in wins over Norwich City and Chelsea.

Just as a serenity had descended over Leeds the year before as United had become flustered, so Cantona’s soothing presence saw United ultimately cruise to the Premier League. They won their last seven games to finish 10 points clear of second-placed Aston Villa.

Even a disciplinarian like Ferguson couldn’t hide his adoration. He accepted Eric’s occasional maverick tendencies, and let him abide by a different set of rules, because he knew it would work. “We all went to a film premiere and were told to wear black ties,” remembers Andy Cole. “Eric turned up in a cream lemon suit and Nike trainers. The manager told him he looked fantastic.”

Luckily, the rest of the squad didn’t resent him. Even Brian McClair, who’d dropped into midfield to make way for Cantona, accepted the situation and knuckled down. The pair combined excellently. Cantona had not divided the squad: in fact, he’d fostered a new togetherness. The club were truly United at last.

The rest, we all know. 1992/93 wasn’t just Year Zero for Eric Cantona, it was Year Zero for England’s biggest club. They would win four titles over the next five seasons; Ferguson would go on to become to become the most successful British manager of them all. And it’s not pushing it to pinpoint it as Year Zero for the box-fresh Premier League, either. “In my eyes, he was responsible for the league developing as quickly as it did,” reckons Schmeichel.

With his popped collar, opaque quotes and none-more-Gallic movie star mannerisms, Cantona was box office before he was actually box office. He was the hero and villain English football needed to grow into the behemoth it is today. Best of all, the nomad had finally settled.

Eric Cantona week on FourFourTwo

• King of the Kop? When Eric Cantona nearly signed for Liverpool

• How Sheffield Wednesday turned down signing Eric Cantona

• Every club Eric Cantona played for: a potted history of the Frenchman's career

• Quiz! Can you name every club Eric Cantona scored against in the Premier League?

Read the inside story of Eric Cantona’s career in the new issue of FourFourTwo magazine

Nick Moore is a freelance journalist based on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. He wrote his first FourFourTwo feature in 2001 about Gerard Houllier's cup-treble-winning Liverpool side, and has continued to ink his witty words for the mag ever since. Nick has produced FFT's 'Ask A Silly Question' interview for 16 years, once getting Peter Crouch to confess that he dreams about being a dwarf.