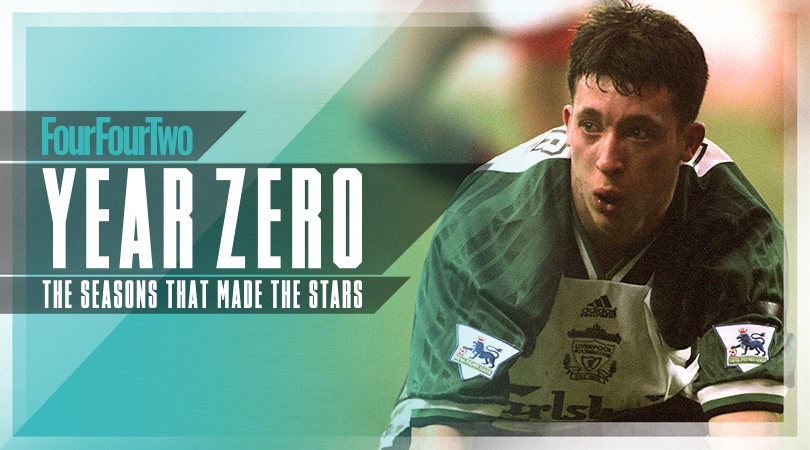

Year Zero: The making of Robbie Fowler (Liverpool, 1994/95)

How could it be that a goalscorer as prodigious as the Toxteth tyro remains so revered, yet also deemed a disappointment? Seb Stafford-Bloor recalls the season 'God' was outed as a Red

Robbie Fowler’s career grew out of political chaos at Liverpool. He may have had the talent to grasp his opportunity, but its timing owed much to the trouble Graeme Souness had created for himself by the late summer of 1993.

Souness’s managerial personality mimicked his playing style. Perhaps too much. Appointed in 1991, he lasted just three years at Anfield and, though that spell yielded an FA Cup win at the end of his first season, the Scot’s time as manager is remembered for its friction and the alienation it caused.

He was too aggressive in his determination to purge established players, losing the trust of some and selling others in his attempts to build a side equipped for the 1990s. Worse, he made a serious error of judgement after his heart bypass surgery by selling the story of his recovery to The Sun. He eventually donated his fee to a local children’s hospital, but – quite understandably – it still bred considerable acrimony.

The Anfield dressing room housed a fog of conspiracies and plotting and, as early as 1992, Souness’s departure seemed to be only a matter of time.

Every cloud

And yet it was that weak position which created the conditions for youth players to graduate. Short as Souness’s reign was, Steve McManaman, Rob Jones, Don Hutchison, Jamie Redknapp, Dominic Matteo and David James were all given first-team opportunities by the Scot. Fowler too, though talented and deserving, also benefited from his manager’s attempts to forge a new team from loyal players and satisfy a crowd that would inevitably gravitate towards their own.

In September 1993, away to Fulham in the Coca-Cola Cup, an 18-year-old Fowler made his first start for Liverpool... and scored his first goal. It set the template for those early, thrilling years. A deep Hutchison cross dropped to him at the far post and, without inhibition or hesitation, Fowler leathered the ball into the roof of the net.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Under different circumstances, that would have been the start of his rise to the top. He kept his place in the team, making his first Premier League start against Chelsea the following weekend, and began to score goals at a ferocious pace – including five at Anfield in the return leg against Fulham, a hat-trick against Southampton, two at Tottenham, and a winner in his first Merseyside derby.

However, a broken ankle sustained in January 1994 hindered his progress. Before he could return, time had run out for Souness: he resigned following a shocking loss to Bristol City at Anfield in the League Cup, and was replaced by Roy Evans.

Evans was a more gentle soul. A Boot Room alumnus hired to cool the scorched earth left by his predecessor and restore the harmony of the previous decade, Evans was initially cautious around his teenage forward and believed that he had been given his debut too young. Within months, he was cheerfully climbing down from that position.

Gunned down

In 1994/95, Fowler’s career pierced the stratosphere. He scored one of Liverpool’s six opening-day goals against Crystal Palace, then eight days required just four minutes and 33 seconds to complete a hat-trick against Arsenal in front of the Sky Sports cameras. The football writer David Lacey referred to it as a “machine-gun rattle of goals”; certainly, the expressions worn on Arsenal faces that day suggested a heavy-shelling.

It was an iconic landmark, one which would stand for over 20 years (Sadio Mane broke it in May 2015 against Aston Villa, thumping his treble in a ludicrous two minutes and 56 seconds) – but it was also the moment at which the brand ironing was pressed to his skin, and from which there was no returning.

“With Sky there and them still trying to pump their coverage for all it was worth to get more viewers, my performance was a gift to them,” Fowler later recalled. “What they wanted were images to their coverage, and idols to sell dishes. I was a goalscorer and I was young, and that season I was hot. So I got the full treatment. I was everywhere, the goals shown over and over again, the papers full of pictures of me, everyone wanting to know about me. I guess that hat-trick cemented me in the public eye.”

“God” was born. Fowler may have returned to his mother’s house that night, picking up some ribs and special fried rice on the way, but the world was changing around him.

Attention and tape recorders

With 20 years of hindsight, it’s easy to overlook the challenges that the young Fowler faced. David Beckham was yet to redefine the way young footballers were covered by the mainstream press. So although the collective lens had already focused on a young Ryan Giggs, the mischievous Lee Sharpe and, to a certain extent, team-mate McManaman, Fowler was stepping into an unexplored environment.

In 2017, developing players are fiercely guarded by press officers and are fluent in platitude from a young age, but 25 years earlier that wasn’t the case: young, unrefined teenagers were thrust onto the stage and into a blinding spotlight. The clubs were just as unprepared as the players, though, and little was done to protect them from the dangers of fame. As David James would recall many years later: “I remember once mentioning the word 'psychologist' at Liverpool. I was later told quietly in a corridor that it was never going to happen, we were Liverpool, and to forget it – all because of some archaic identity that we could never change.”

The anecdotes Fowler tells from that time are also descriptive, with one in particular describing the naivety of that time. During a scheduled interview with a men’s magazine, he and McManaman – believing themselves to be out of earshot when the journalist in question left the room – got “creative” with their answers to the prepared questions. Alas, a whirring tape recorder had captured their conversation, with all its boyish snark and japery, and their antics had put them in the middle of a major controversy.

It was the kind of trap which today’s young professionals, guided at all times by media advisors, would never fall into. Back then, however, footballers were yet to realise that they were never really off the record.

Robbie's repertoire

The attention didn’t smother his form, though. By the time 1994 turned to 1995, Fowler had scored 18 Premier League goals. Other than the Arsenal hat-trick, two goals linger in the memory, both of which came against Aston Villa at Anfield.

The first, a rising, full-blooded drive into the top corner from the edge of the box, castled Mark Bosnich with its flummoxing power. The second, from similar range but tickled gently into the bottom corner, was precisely placed beyond the Australian’s reach.

4:12 for the brilliant first; No.2 at 7:20

Within that contrast lay part of Fowler’s appeal. He was an ordinary teenager from a local estate, the Boy King of Merseyside, but he was also a goalscorer of great variety. Those who paid to watch him, or who just tuned it at the right time each week, didn’t know what they were about to see. While other contemporary forwards specialised in scoring particular type of goals, Fowler’s trademark was his diversity: inside the box or outside, power or finesse, left foot, right foot or with his head.

On December 28, he ripped a swirling long-ranger into the top corner against Manchester City at Anfield. Three days later, he ran beyond the Leeds defence at Elland Road and converted his one-on-one with a calm side-footed finish.

00:20 for the latter goal

That was him. When his name flashed up on teletext, nobody knew quite what the Match of the Day cameras might have caught.

Regarding his fame, Fowler was right in one sense: Sky needed stars to sell their dishes and he was elevated to play a certain part. From another perspective, though, the costume he wore fitted perfectly: he embodied entertainment at a time when it was becoming a marketing imperative.

Head in the Sky

The 1994/95 season might be principally remembered for Fowler’s goals, as the majority of his early career is, but he was always slightly more than a centre-forward. He abhorred the media attention away from the field and has confessed to never being entirely comfortable with the public’s attention either, but his performances were never affected.

Certain incidents have endured, particularly those which attracted the FA’s attention, but Fowler was generally full of emotional expression on the pitch. He loved scoring goals, that much was obvious, but he seemed energised by the spectacle itself; the Toxteth lad was cheeky and uninhibited, an advert for just how much fun professional football could be.

What was really amazing about Robbie is that he didn’t look like an obviously great player

Fowler was also highly normal, both in the way he looked and how he played. John Barnes once made the observation that “what was really amazing about Robbie is that he didn’t look like an obviously great player. He wasn’t particularly quick, or tall or skilful, and I remember when he moved from the youth set-up to the first team he was very awkward in his manner on and off the pitch.”

Relatability is important. The early 1990s may have seen the birth of the footballing superstar, but the widening financial distance between players and supporters created a sense of unease. Fans may have wanted their heroes to perform superhuman feats, but they also craved the reassurance that, really, they were still just like them.

Somehow, Fowler struck that balance. Beckham would win the pop star wife and the modelling contracts, Jamie Redknapp followed suit and – hilariously – even Jason McAteer dallied in shampoo commercials, but Fowler remained distinctly ordinary. As the goals flew in and his reputation grew, he retained a texture which belied his celebrity and allowed his star to burn yet brighter.

Beginnings and endings

Liverpool’s star eventually waned, though. As would be their association through most of the decade, they fell away towards the end of that season. Coventry and Leeds both won at Anfield in April and the Reds also lost comprehensively at Aston Villa and West Ham in May.

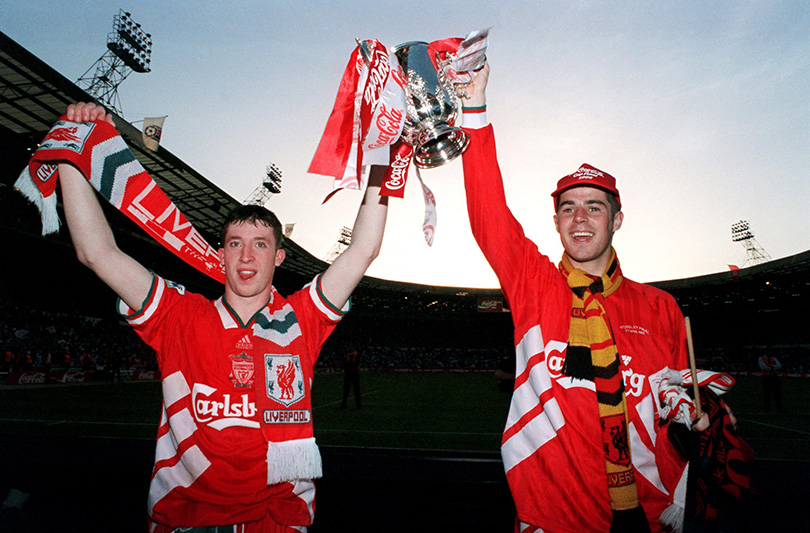

By that point, however, a pair of Fowler goals had taken Evans’s team to Wembley for the Coca-Cola Cup final, where a virtuoso McManaman performance against Bolton helped Liverpool to a 2-1 win. It was a first senior final for Fowler, and his first silverware as a professional.

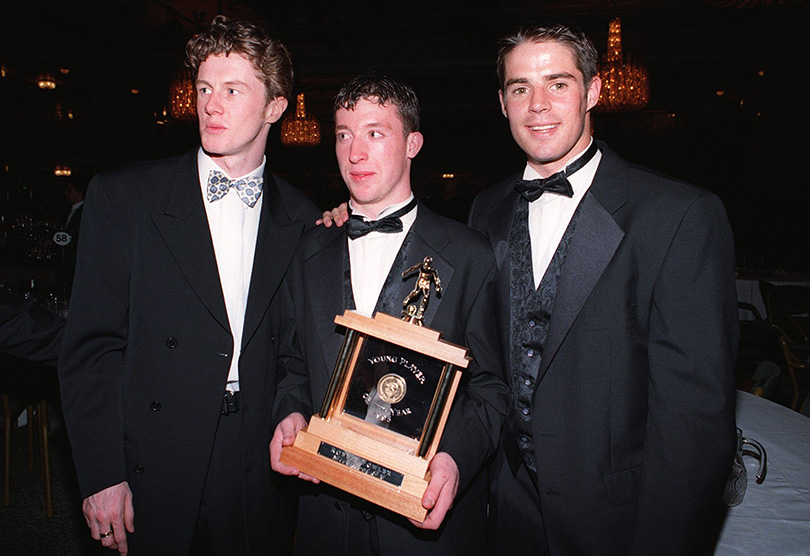

The PFA Young Player of the Year award followed (the first of two in a row), presented to him by a beaming, almost paternal Ian Rush, and acted as apparent confirmation that he had entered permanent orbit. Fowler was a star of the game, one of the most watchable players in Europe. With 31 goals in all competitions, he also looked like the most natural finisher of his generation.

But if 1994/95 was the beginning, then the following season was really the beginning of the end. Another 28 Premier League goals later, Fowler was heading to Euro 96 with England and a step closer to football’s summit.

But he would never get any closer. Injury blunted his dynamism and an antagonistic relationship with Gerard Houllier eventually necessitated his sale to Leeds for £12m in 2001. There was a before and after, without question, and the years following – though still decorated with goals – only heightened the regret over what had been lost.

It is to his credit, though, that over two decades later Fowler is still inextricably bound to his best form, to Martin Tyler’s many inflections, and to one of the most incendiary beginnings to a career that English football has ever witnessed.

“One morning I came down to breakfast and my face was on the back of the cornflakes box," Fowler later remembered. "Weird.”

Like this? More Year Zero...

- David Beckham (Manchester United, 1996/1997)

- Dennis Bergkamp (Ajax, 1986/87)

- Ronaldinho (PSG, 2001/02)

- Ronaldo (Barcelona, 1996/97)

- Frank Lampard (Chelsea, 2004/05)

- Thierry Henry (Arsenal, 1999/2000)

- Cristiano Ronaldo (Manchester United, 2006/07)

- Zinedine Zidane (Juventus, 1996/97)

- Gareth Bale (Tottenham, 2010/11)

- Eric Cantona (Leeds/Manchester United, 1992/93)

Seb Stafford-Bloor is a football writer at Tifo Football and member of the Football Writers' Association. He was formerly a regularly columnist for the FourFourTwo website, covering all aspects of the game, including tactical analysis, reaction pieces, longer-term trends and critiquing the increasingly shady business of football's financial side and authorities' decision-making.