Football’s ultimate cult clubs

We pick out football’s 24 ultimate cult clubs

Football's biggest cult clubs

Every once in a while, a team comes along and wins the hearts of the football world. Trophies certainly help to boost these sides’ legends, but most are heralded because they have a distinct style, a collection of characters or an impressive list of underdog achievements.

In this slideshow, we pick out football’s 24 ultimate cult clubs…

Barcelona (1990-94)

It took Johan Cruyff’s vision to change La Masia into the paragon of skill-over-physicality philosophy from 1988 – Lionel Messi, Xavi and Andres Iniesta are all under 5ft 9in – realising a production line of technical waifs which turned Barcelona into football’s aesthetes.

Dubbed the Dream Team after sealing the Catalans’ maiden European Cup win in 1992, the side Cruyff built also won four consecutive La Liga titles from 1990/91. Koeman, Laudrup, Stoichkov and later, Romario – this is the team Blaugrana fans get misty-eyed about, not the 2009 or 2011 vintages with those three Lilliputians.

“Cruyff reinvented the concept of football in Spain,” centre-back Miguel Angel Nadal once told FFT. He wasn’t wrong.

Borussia Dortmund (2011-15)

His gurning visage is now a semi-permanent fixture, but it was in Westphalia where the cult of Jurgen Klopp first began converting non-believers. It was a slow process – Dortmund were in financial trouble when Klopp took charge – but seeing starlets Mario Gotze, Mats Hummels and Sven Bender establish themselves alongside bargain recruits Shinji Kagawa and Robert Lewandowski was a perfect antidote to the ‘against modern football’ crowd.

With the cheapest season ticket available for £160 and atmosphere created by the Yellow Wall, it didn’t take very long for most of Europe to adopt Dortmund as their second team. Success – back-to-back Bundesliga titles in 2011 and 2012, plus the 2012 German Cup and a thrilling run to the 2013 Champions League Final at Wembley – was the least they deserved.

Bayer Leverkusen (2001-02)

After consecutive finishes of second, third, second, second and fourth, including a title lost on goal difference when they couldn’t manage a final-day draw, Leverkusen finished 2001/02 as runners-up in three competitions. Football’s cruel sometimes.

But it was this near-magical season that crystallised their cult status. Ze Roberto was sensational on the wing and Michael Ballack hit 21 non-penalty goals from midfield, driving into space left by tiny roaming forward Oliver Neuville. If anything, their second-place Bundesliga finish and defeats in the finals of the Champions League and DFB-Pokal only added to their appeal.

Boca Juniors (2000-03)

Dressed in a kit bordering on the pornographic, Carlos Bianchi’s Boca Juniors team at the turn of the 21st century were thrilling. Young tyros Nicolas Burdisso, Walter Samuel and penalty-missing fan Martin Palermo drenched La Bombonera in defensive steel and attacking zeal, but it was hipster wet dream Juan Roman Riquelme who brought naughty thoughts to beardy Shoreditch types. “Riquelme’s brains,” said football philosopher Jorge Valdano, “save the memory of football for all time.”

Boca bagged back-to-back Copas Libertadores and the Intercontinental Cup, beating Real Madrid 2-1 in Tokyo. They then won another Libertadores in 2003, led by Carlos Tevez, a mongrel to his predecessor’s Mozart.

New York Cosmos (1975-80)

In 1974, the NASL All-Star Team’s biggest name was former Weymouth defender Dick Hall (four USA caps, four defeats). In 1977, the All-Stars XI featured Franz Beckenbauer, George Best, Gordon Banks and the man who directly or indirectly brought them Stateside: Pele.

It took the Cosmos four years to sign the Brazilian in 1975, but he – alongside Beckenbauer and former Lazio striker Giorgio Chinaglia - had the desired impact. OK, they won nothing for two seasons, but people watched them win nothing, and they epitomised cool: their kit was an instant classic, film stars attended matches and Mick Jagger was a dressing-room regular.

Arsenal (1989)

Arsenal travelled to Anfield for the final game of the 1988/89 season – the original clash was postponed in the aftermath of Hillsborough – knowing they needed to beat Double chasers Liverpool by two goals to win the First Division they had at one point led by 15 points.

Michael Thomas’ dramatic winner provided a timely reminder of English football’s positives. True, the Gunners weren’t particularly pleasing on the eye – this was peak ‘1-0 to the Arsenal’ of Dixon, Adams, Bould, O’Leary, Winterburn – but football was back on the front pages for the right reasons, as Arsenal handed flowers to fans and donated £30,000 to the Hillsborough Disaster Fund. This was the moment English football woke up.

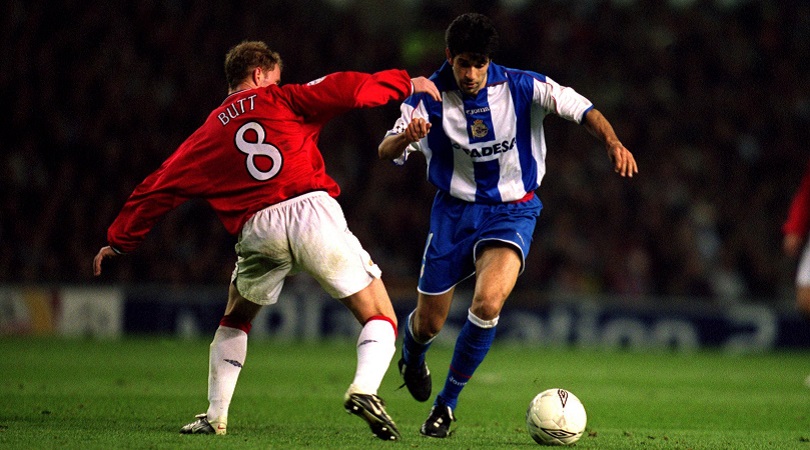

Deportivo La Coruna (1999-2002)

Deportivo in the late-90s were the footballing version of Katherine Heigl in rotten 2008 chick-flick 27 Dresses – always the bridesmaid, never the bride. But just like Heigl, their day would come.

You would generously label Donato and Mauro Silva as experienced, while Spurs fans will admit Noureddine Naybet wasn’t the most consistent centre-back and playmaker Djalminha seldom exerted himself. But the Spaniards sure could play; Real Madrid and Barcelona had won 14 of the previous 15 league titles at the start of 1999/00, but under Javier Irureta the underdogs defied the behemoths, thanks to Augusto Cesar Lendoiro’s mini-Galactico investment. Throw in Juan Carlos Valeron, the Spanish Riquelme, and you’ve got quite the team.

Dundee United (1982-87)

Name the only side that can boast a 100% win record against Barcelona over more than one fixture. Yep: Dundee United have faced the Blaugrana on four occasions, and won all four. It’s the latter two victories, in the quarter-finals of the 1986/87 UEFA Cup, which Tangerine fans savour most.

Underpinned by the talented up-and-at-em trio of Paul Sturrock, Maurice Malpas and David Narey, United had already reached the semi-finals of the European Cup three years earlier, after winning the Scottish title ahead of Celtic. Manager Jim McLean was the mastermind; an abrasive character not dissimilar to Brian Clough, the ex-Clyde and Dundee striker used to call his players the night before a game, to prove they weren’t out.

Dynamo Kiev (1985-86)

Football statistics are ubiquitous these days; more than any other team, Dynamo Kiev are responsible for such proliferation of numbers. Under Valeri Lobanovskiy, the Ukrainians developed a scientific approach in which each player was asked to perform 100 different actions in a match. The next day, a piece of paper would be pinned to the wall revealing everyone’s stats. Anyone not up to scratch would be dropped.

Over three spells spread across 20 years, Lobanovskiy lifted 29 trophies including a dozen league titles. It was the second spell which truly secured Dynamo’s cult appeal: led by Oleg Blokhin and Igor Belanov, the side which clinched the 1986 Cup Winners’ Cup was the perfect example of Lobanovskiy’s cause-and-effect interpretation of football chess.

Athletic Bilbao (1921-25)

“Con cantera y aficion, no hace falta importacion” is the Basques-only motto by which Athletic Bilbao live – with the youth team and fans, there’s no need for imports. Despite the limitations that rule imposes, they’ve still played in every top-flight Spanish season.

Their most memorable vintage came in the 1920s, before Spain even had a national league system. The nephew of author Miguel de Unamuno, Rafael ‘Pichichi’ Moreno was a slightly-built scoring machine who always wore a knotted handkerchief on his head. Pichichi’s 83 goals in 89 Athletic appearances secured five Basque titles – plus four Copas del Rey, effectively the biggest prize in Spain – to make him the country’s first football hero. Spain's top-scorer prize is named after him.

Estudiantes (1967-70)

Estudiantes won the 1967 Metropolitano, then three consecutive Copa Libertadores titles and an Intercontinental Cup. Led by former Argentina manager Osvaldo Zubeldia, they were arch Machiavellian pragmatists – the ends always justified the means. “You don’t arrive at glory through a path of roses,” Zubeldia once huffed.

Midfield engine Carlos Bilardo was his boss’ on-field anti-futbol lieutenant, frequently taping pins to his wrist to jab into opposition ribs at set-pieces. But the Rat Stabbers (yes, really) could play, too. Dubbed La Tercera que Mata by the Argentine media (the Kids who Kill), Estudiantes pioneered a high press and could count on Juan Ramon Veron (Juan Sebastian’s dad) to provide the guile.

Flamengo (1981)

Nicknamed O Mais Queried do Brasil – the most beloved team in Brazil – Flamengo are their nation’s best-supported, and one of their richest, outfits. They have had several good vintages, but the early-80s were the apex: they scooped their first Campeonato Brasileiro in 1980, and the following year captured both the Copa Libertadores and Intercontinental Cup.

In a side crammed with creativity, this Flamengo became known as the Geração de Ouro – Golden Generation – and are arguably the finest South American side ever. Zico was their beating heart: fast, two-footed and a real bag of tricks. “I never got anywhere near him,” admitted Graeme Souness, who was part of the Liverpool team beaten 3-0 in the Intercontinental Cup Final.

Borussia Monchengladbach (1970-79)

This Borussia Monchengladbach team featured gloriously attacking youngsters, many recruited from within a 10-mile radius of the German city near the Dutch border. Luxuriously talented (and coiffed) playmaker Gunter Netzer captured everyone’s imagination, with full-back attack dog Berti Vogts and pathological winner Jupp Heynckes the steel behind five Bundesliga crowns (including three in a row from 1975) and two UEFA Cups.

They may have lost to Liverpool in the 1977 European Cup Final, but it’s not hard to see why Gladbach so enthralled fans everywhere. Their 5-1 defeat of Twente in the 1975 UEFA Cup Final second leg was the closest thing to Total Football the German game has ever seen.

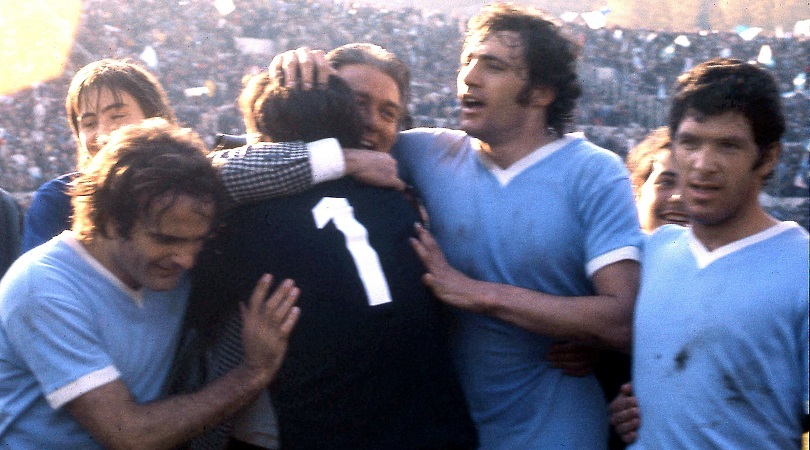

Lazio (1972-77)

Internal hostilities were frenzied in the Lazio dressing room during the mid-70s. “Everyone detested each other,” recalled goalkeeper Felice Pulici. Legend has it, the squad would only wear shinpads in training – not bothering for games – so violent were the sessions. “By the time you played a league match, it felt like a friendly,” quipped midfielder Luigi Martini.

Tooled-up players started a part-time shooting club to have a pop at “things in bushes and bits of furniture”, while striker Giorgio Chinaglia destroyed a training ground shed with his 6.5mm rifle. In between the gun-toting japery, a forward-thinking football team broke out, and the Eagles won Serie A in 1974.

Middlesbrough (1996-97)

Signing £7 million Fabrizio Ravanelli – fresh from scoring in Juventus’ Champions League triumph against Ajax – and Brazilian midfielder Emerson in 1997 was one of the Premier League’s biggest transfer coups for a Middlesbrough side who already possessed pint-sized Samba waif Juninho buzzing about in a six-sizes-too-big bedsheet. And Craig Hignett and Phil Stamp.

Despite murmurings of discontent off the pitch – “they have a Ferrari, but no garage,” huffed self-referencing Ravanelli of the battered team bus – Boro proved the talent was there by reaching both cup finals. But they lost both, and then went down.

Napoli (1984-1991)

Seven years with Diego Maradona brought Napoli their two Serie A titles and only continental trophy. They’d avoided relegation by just a point when he arrived for a world-record £6.9 million fee. It was football’s most transformative transfer, from the moment 75,000 fans watched him land at Stadio San Paolo in a helicopter.

They won a league and cup Double in 1987 and beat Milan to the title in 1990, Diego schooling their famous defence in a 3-0 humbling. If Juventus and both Milan clubs were dull, clean-cut suitors to your sister, Maradona’s Napoli represented the rebel with bad habits. When they clinched that first Scudetto, graffiti in a graveyard proclaimed, ‘Guys, you don’t know what you’re missing’.

Norwich City (1992-94)

Two words: Jeremy Goss. If you were watching football in the early-90s, you’d understand. The season before the game forever associated with Norwich in Bavaria, the Canaries ran Manchester United close in the first Premier League campaign thanks to a mixture of club stalwarts like Ians Culverhouse and Crook, and promising up-and-comers such as Ruel Fox and Chris Sutton.

It’s in the 1993/94 UEFA Cup Second Round, though, where Delia’s finest truly earned their cult status. The Canaries’ 2-1 victory in the Olympiastadion made them the first British team to defeat Bayern Munich in their own backyard, before succumbing to a brave 2-0 aggregate loss to Dennis Bergkamp’s Inter.

Parma (1992-99)

In 1992, Parma got their first taste of silverware and liked it. So, the Coppa Italia in the bag, they brought in Tino Asprilla, who embodied this flair-filled side. Gianfranco Zola, Fernando Couto, Dino Baggio, Tomas Brolin and Hristo Stoichkov came later, while a teenage Gianluigi Buffon kept a clean sheet on his debut against a Milan team with two Ballon d’Or-winning strikers.

Two factors raise their cult appeal abroad: Channel 4 launching Football Italia in ’92, and unfulfilled potential. Parma weren’t loveable losers. They won eight trophies, their only eight trophies, within a decade, but lost the 1996/97 Serie A title to Juventus by two points.

River Plate (1941-47)

Nicknamed La Maquina (the Machine) by El Grafico journalist Borocoto, this was an ethereal River vintage at a time when South American football already felt like it was from another planet. Still in the era of the 2-3-5 formation, frontline Juan Carlos Munoz, Jose Manuel Moreno, Adolfo Pedernera, Angel Labruna and Felix Loustau switched their positions with such bewildering regularity – Moreno and Pedernera dropping deep into midfield – that defences were tied in knots.

They lifted 10 major honours and became known as los Caballeros de la Angustia, or Gentlemen of Anxiety. Some claimed it was because of a habit of freezing in cup finals, but Moreno argued that it was “because we could score at any moment. Our opponents knew it”.

Saint-Etienne (1973-77)

Decked in bottle green to match the colours of their founders, grocery chain Groupe Casino, Saint-Etienne of the mid-1970s were the louche mining newbies taking on the established order of Stade de Reims, Nice and Monaco.

The son of an oyster farmer, ‘Green Angel’ Dominique Rocheteau sashayed down the right wing, future Spurs boss Jacques Santini added midfield legs and Jean-Michel Larque goals. Under manager Robert Herbin they won three successive titles, and were only denied 1976 European Cup glory against Bayern Munich by Hampden Park’s infamous square goalposts.

Tranmere Rovers (1990-95)

After winning promotion to the Second Division in June 1991 – via the play-offs, their fourth trip to second home Wembley in 12 months – Tranmere recruited John Aldridge from Real Sociedad for £250,000. Two years later, ultimate cult footballer Pat Nevin – who once had a column in the NME – arrived, forming a glorious front four in which he and John Morrissey flanked Aldridge and Chris Malkin.

“I can’t promise anyone success,” said boss Johnny King, “but I can promise a trip to the moon.” In the end he delivered the former, if not the latter. Three times they reached the play-offs and a shot at promotion to the Premier League, only to fall short.

Valencia (1998-2004)

Valencia’s success around the turn of the millennium began with the Copa del Rey. Claudio Ranieri won Valencia’s first major trophy in 20 years in 1999, Claudio Lopez spearheading a goal-hungry side that scored 21 times in seven games, including a 6-0 demolition of Real Madrid.

Post-Ranieri, Hector Cuper then reached consecutive Champions League finals by making Valencia’s Mestalla home a fortress. They lost in both showpieces but bounced back under Rafael Benitez, winning two league titles and lifting the UEFA Cup to boot. They even picked up the Fair Play award. Sometimes nice guys do finish first.

Wimbledon (1984-88)

It’s easy to adore Barcelona, Ajax, Borussia Dortmund and other hipster teams with all their passing, talent and general bonhomie. Less so a bunch of pyromaniac neanderthals from London, who insist on agricultural football, excessive force and eating sheep’s testicles. Wimbledon, it’s fair to say, were different.

The Dons went from the Fourth Division to the First in four seasons courtesy of a ferocious team spirit and the abilities of former hod carrier Vinnie Jones, ex-Barnardo’s boy John Fashanu and pint-sized scamp Dennis Wise. Pretty it wasn’t – “the best way to watch Wimbledon is on Ceefax,” huffed Gary Lineker – but Wimbledon finished as high as sixth in the top flight in 1986/87 and then achieved immortality by stunning Liverpool in the following season’s FA Cup Final.

Greg Lea is a freelance football journalist who's filled in wherever FourFourTwo needs him since 2014. He became a Crystal Palace fan after watching a 1-0 loss to Port Vale in 1998, and once got on the scoresheet in a primary school game against Wilfried Zaha's Whitehorse Manor (an own goal in an 8-0 defeat).