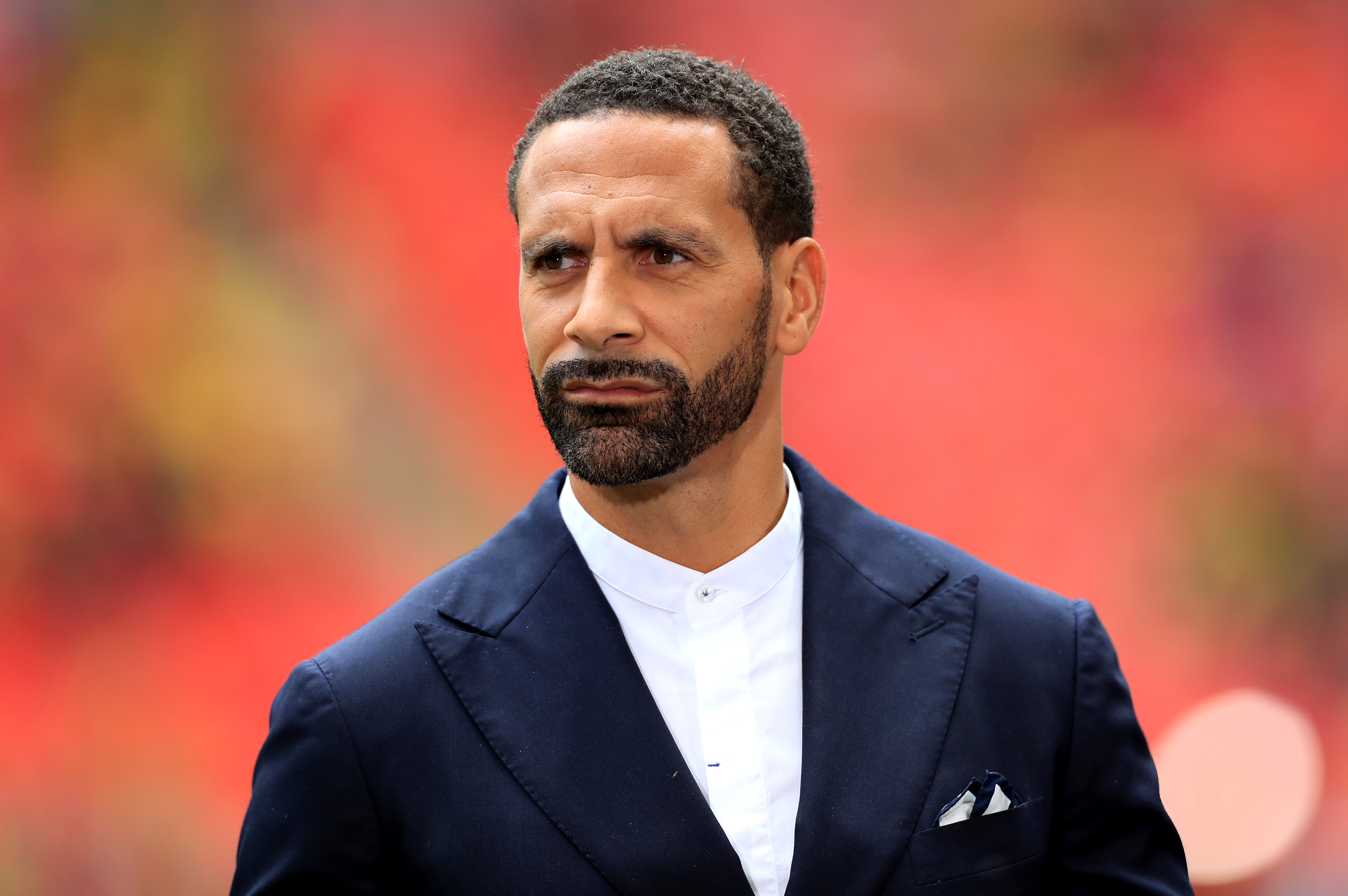

Rio Ferdinand reveals how online abuse had major impact on his family

Rio Ferdinand has revealed how members of his family would “disintegrate” at seeing online abuse aimed at the former England and Manchester United defender.

Ferdinand gave evidence to a joint committee of MPs and peers seeking views on how to improve the draft Online Safety Bill designed to tackle social media abuse.

His brother Anton had told the Home Affairs Committee on Wednesday that in his view the social media companies would not act on online abuse until a footballer or celebrity took their own life, by which time it would be too late.

Ferdinand spoke openly about how the abuse can impact individuals and their families.

“When you sit at home and you look on there and there’s negative discrimination and prominent for you to see, self-esteem and your mental health is at risk,” he said.

“And again, it’s not just about that person, it’s the wider network of that person and what it does to family and friends.

“I’ve seen members of my family disintegrate at times, I’ve seen other sports stars’ family members taking it worse than the actual person who’s receiving the abuse.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Ferdinand felt too much of the onus to block abusers lay with the victim.

“I think that’s an easy cop-out for the social media platforms when they put forward ideas like that,” he said.

Ferdinand felt it was “baffling” that social media companies could act so quickly on issues around copyright but could not be so proactive on discrimination.

He said there was a “disheartening” inevitability about the abuse directed at England trio Marcus Rashford, Bukayo Saka and Jadon Sancho after the penalty shoot-out defeat to Italy in the final of Euro 2020 at Wembley in July.

He said: “When those three players missed those penalties, the first thing I thought was ‘let’s see what happens on social media’. I expected (the abuse) to happen.”

Ferdinand cited what he felt were the lack of consequences for online abuse, compared to in-person acts.

He said someone would be identified and punished for throwing a banana onto the pitch, but added: “Online you can post a banana (emoji) and be fine. There are no repercussions. How can that be right?”

Edleen John, the Football Association’s director of international relations, corporate affairs and equality, diversity and inclusion, suggested a “layered” approach to accessing platforms where people could not or would not share identity verification.

Looking forward to joining the session tomorrow chaired by @DamianCollins and giving evidence on behalf of all of football alongside @SanjayKickItOut & @rioferdy5. We welcome the chance to work with government to #StopOnlineAbuse and ensure safe spaces online for all @FAhttps://t.co/Lb4QO9yQ79— Edleen John (@edzj_13) September 8, 2021

“When it comes to verification, social media companies seem to believe that it’s a binary option, an on-off switch where people have to provide all information or no information,” John said.

“What we believe is that there are multiple layers and multiple mechanisms which could be used in combination that could be used to tackle this issue.

“ID verification is one element, default settings could be another, the limiting of reach could be another.

“The reason we think it has to be a layering is because when we look at the volume of abuse that is received across the world of football, we see that a lot of the abuse is coming from ‘burner’ accounts, where people set up an account, send abusive messages, delete an account and are able to re-register another account within moments.”

John described the regulatory systems put in place by the social media companies themselves akin to “putting a band-aid over a bullet wound”.

As we head into the weekend, find out about all the ways you can report instances of discrimination to us 👉🏽 https://t.co/kSwM0jH9Ulpic.twitter.com/3pteseMWMM— Kick It Out (@kickitout) August 27, 2021

Kick It Out chair Sanjay Bhandari told the committee there was a clear disconnection between the social media companies’ European management and their American headquarters.

“My experience is we will have conversations in London, and it will be London says ‘oh, that’s interesting, maybe’ and then California says ‘no’,” he said.

“I’m not sure if I’m stuck in Groundhog Day or Dante’s Inferno. Either way, it’s a deeply unpleasant experience.”

Bhandari said access to platforms was currently too frictionless and added: “It’s too easy for someone to just turn up and abuse someone.

“We have to remember that the online world of abuse is not someone standing on Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park and shouting abuse into the ether.

“This is 150 people in a Twitter pitchfork mob turning up in your living room and spitting abuse in your eyes, whilst your family are next door, unable to do anything about it. That’s the problem that we’re dealing with and that’s the problem we need to address.”

Bhandari said legislation would need to anticipate new methods of abuse.

“We are not legislating for the world as it is now, we also have to legislate for the world as it is going to be and we can’t anticipate all of those changes,” he said.

“So the best thing to do is to give Ofcom the power to do that.”

Imran Ahmed, the chief executive from the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) said social media giants had proved “incapable of regulating themselves” and that at every turn they “put profit before people.”