Ivory Coast could make AFCON a story for the ages – but Africa's dream of hosting another full World Cup may be a way off

FFT's senior staff writer headed to Abidjan for the Africa Cup of Nations, and assesses the chances of the continent being chosen again as sole hosts of the globe's biggest tournament

The noise around the Alassane Ouattara Stadium was deafening, as Sebastien Haller hooked home the only goal of the game on Wednesday night, and sent Ivory Coast into the final of the Africa Cup of Nations, thanks to victory over the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

More than 50,000 people had created a passionate sea of orange, inside an impressive three-tier stadium built specially for the country's first hosting of AFCON since 1984.

Ivory Coast has been through two civil wars since then – if the long wait to stage another tournament had already generated no shortage of excitement when AFCON began last month, the circuitous route the home nation have taken to the final has only made that excitement more frenzied.

The Elephants looked set for an early exit from the competition after losing two of their three group games, firstly to Nigeria, then shockingly 4-0 to Equatorial Guinea, in what looked a nation-scarring meltdown akin to Brazil's 7-1 defeat to Germany in 2014.

Ivory Coast actually had 68 per cent possession, but everything that could go wrong did – two goals disallowed for offside by VAR at crucial moments, then ruthless counter-attacking from their opponents, with some home fans trying to get on to the pitch to express their anger at how events had unfolded.

Finishing third in their group, French coach Jean-Louis Gasset exited as they waited two days for their expected elimination – only to somehow squeak through to the last 16 as the fourth best third-placed team, largely because Ghana improbably threw away a two-goal lead against Mozambique in injury time.

Under interim coach Emerse Fae, once a midfielder for Reading, Ivory Coast equalised late on against holders Senegal in the last 16, before triumphing on penalties, then came from a goal down to beat Mali with 10 men in the final minute of extra time in the quarter finals. By comparison, a 1-0 win over DR Congo in the semis seemed positively serene.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Ivory Coast's journey has made this AFCON – had they gone out in the group stage, enthusiasm for the tournament in the country probably would have waned severely. But the host country has also been one with a point to prove, rebuilding after political strife, eager to show themselves to the continent, and indeed the world.

I spent a few days in the country at the start of the tournament – one of the group games I took in, Ivory Coast versus Nigeria, has turned out to be the final, too. Just as it will be on Sunday, it was played at the huge Alassane Ouattara Stadium, built at the cost of £200m on the far outskirts of Abidjan.

“This stadium is fantastic," Ivorian journalist Salia Drame, of Abidjan Sport, told me then. "We hope all of black Africa gets these kinds of stadiums and we maybe try to host a World Cup one day. That’s our hope – to share with Ghana and Nigeria, plus Senegal is near."

There's no doubting that west Africa would embrace a World Cup if they ever got the chance – during my trip, it was abundantly clear how much people in Ivory Coast loved football.

Wherever you went, you saw people in football shirts – as well as many in the jersey of the national team, I saw people in shirts as disparate as Manchester City, Newcastle, Rangers, Nottingham Forest, Hull, PSG, Galatasaray, Inter Miami and Al Nassr.

Bars on every corner were packed with people watching AFCON games on TV, and taxi drivers told me how they'd be listening to the radio intently when the matches were on – their work making it impossible for them to get to the stadium themselves.

Only one World Cup, 2010 in South Africa, has ever been fully hosted by the African continent though, and the prospects of that changing soon don't look great.

Morocco made bids to host the tournament in 1994, 1998, 2006, 2010, 2026 and 2030, before eventually accepting an offer to co-host 2030 with Spain and Portugal, who look likely to be the dominant partners in that relationship.

The two European nations were already fancied by many to win hosting rights, even without Morocco's involvement – they'd previously invited recently-invaded Ukraine to join their bid, before switching to the African nation instead.

The cynic would suggest they were probably aware that adding Morocco would bring support from a number of African federations, helpful in getting their campaign over the line.

That Uruguay, Argentina and Paraguay will also oddly host three matches at the start of the 2030 tournament speaks to the state of play in football these days – the South American nations had bid to host the tournament outright, as a centenary celebration of the first ever World Cup, held in Uruguay in 1930.

But today, hosting football tournaments often comes down to having cold hard cash, something South America isn't always overflowing with.

That remains a big problem for Africa, too, when trying to wrestle the World Cup away from the likes of Europe, the US or the Middle East.

Once previous hosts South Africa are discounted, Morocco seemed like pretty much the continent's best hope, but had to settle for a compromise deal.

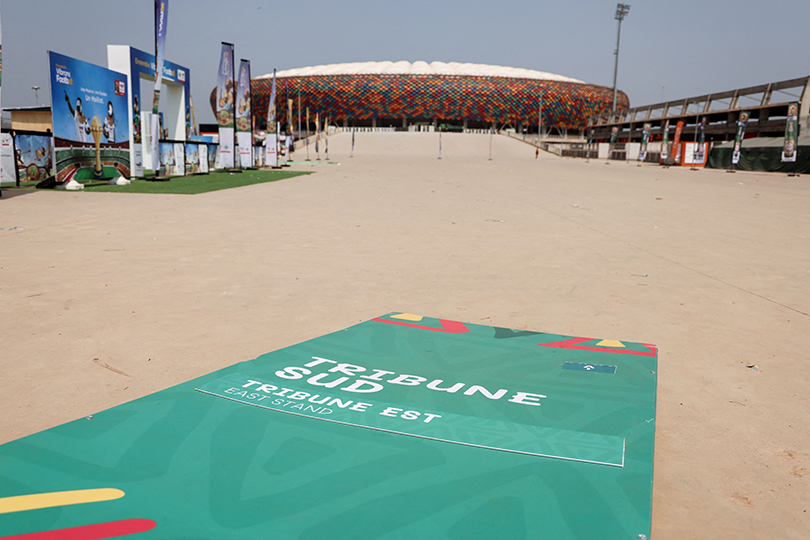

Certainly Ivory Coast didn't look ready to host a World Cup during my visit, as welcoming and enthusiastic as everyone was, and as fascinating as it was to visit such a different country.

It was chaos at times, with people absolutely everywhere, and nothing running quite as smoothly as it would in Europe. But somehow it was a beautiful chaos.

Only two of the stadiums used for AFCON have been over the 40,000 capacity usually required for a World Cup though, and travel between cities was not easy.

Other problems that AFCON has suffered in recent times would also probably make FIFA nervous – even the event’s location has often been uncertain. Libya were due to stage the 2013 tournament, but withdrew because of civil war, then again in 2017.

Plans for Morocco to host in 2015 ended when west Africa’s Ebola epidemic made them reluctant, then rebel violence and preparation delays saw Cameroon stripped of 2019.

West Africa's summer rainy season also forced this tournament, officially called ‘AFCON 2023’, to be moved to January and February 2024.

Sadly, AFCON has suffered tragedies, too: three were killed when gunmen attacked the Togo team bus in Angola in 2010, while eight died in a crush to access the new 60,000 Olembe Stadium when Cameroon finally hosted in 2022.

Thankfully, there have been no such issues at the current tournament – security was noticeably extremely tight around stadiums, with only people with tickets allowed anywhere near the venue, and no chances taken.

Ivory Coast will face a stern test to avenge their group-stage defeat to Nigeria in Sunday's final – the Super Eagles have Victor Osimhen up front, after all.

Staging a World Cup may be out of reach for the hosts for now, but they've embraced this tournament, and made it one to remember.

Succeed in the final, and their team will have written one of the greatest comeback stories in AFCON history. Succeed in the final, and they'll be talking about this in Ivory Coast for decades.

Read this month's FourFourTwo magazine, available in shops now, for Chris Flanagan's full six-page feature about what it was like to go to AFCON, featuring goats, Supertramp, Didier Drogba and plenty more

More AFCON stories

Quiz: the top goalscorer from each AFCON since 2000

Why did Egypt officials sacrifice a cow at the Africa Cup of Nations?

Chris joined FourFourTwo in 2015 and has reported from 20 countries, in places as varied as Jerusalem and the Arctic Circle. He's interviewed Pele, Zlatan and Santa Claus (it's a long story), as well as covering the World Cup, Euro 2020 and the Clasico. He previously spent 10 years as a newspaper journalist, and completed the 92 in 2017.