How clubs are toughening up young players

Old school training camps, mobile phone bans and psychology workshops are helping clubs to toughen up their academy players

It’s a sweltering day in late July and a squad of teenage footballers runs wearily through the Lake District, each carrying a log above their head. At the end of a muddied trail, the group dives into a river and swims downstream.

The players must rely on their own acumen and the moral support of their team-mates to overcome each challenge. There are no player liaison officers on hand to solve problems, nor any sports psychologists present to massage bruised egos.

Related story: What it takes to become an academy player

For three days, contact with the outside world is limited. All electrical devices - mobile phones, iPads, and laptops - are banned, with players made to fill their free time by listening to motivational speakers at mental resilience workshops.

Sheffield Wednesday’s under-18 side are undergoing a punishing boot camp. It is designed to build resilient characters capable of overcoming adversity on the pitch and reverse a worrying trend threatening to spread through football.

A month earlier, the national team’s embarrassing 2-1 defeat to Iceland saw them exit Euro 2016 at the group stage. Critics claimed the national side’s pampered millennials were mentally weak and incapable of dealing with difficult situations.

A verbal gem from an exasperated Chris Waddle saw the former England winger lash out at a perceived lack of character. “They’re all just headphones,” he wailed, while wearing a pair for commentary duties as a BBC Radio 5 Live pundit.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

But, he may have had a point. Sheffield Wednesday’s under-18 coach Danny Cadamarteri tells FFT: “On my first day at the club, all the youth team players were sat in silence in the dressing room with their headphones on, scrolling through Facebook, Instagram and Twitter on their mobile phones.”

Modern players can spend more than 10 years being nurtured inside the incubators of state-of-the-art academies. An army of staff is then available to tend to their every need once they achieve footballing adulthood. But, has this cotton wool existence made footballers soft?

It wasn’t like this in Trevor Brooking’s day. “When I was a player we made our own decisions,” the 67-year-old declares to FFT. “Players don’t make decisions for themselves now. The clubs hire people to do everything for them. If you don’t make decisions for yourself off the pitch, you won’t make them on it.”

The tale of Adam Morgan is a cautionary one for players and clubs. The striker joined Liverpool aged five and was described by Reds legend Robbie Fowler as “one of the best finishers I’ve seen for years” after scoring 18 goals in 16 youth team games in 2010-11.

But, his Anfield story does not have a happy ending. In 2013, Liverpool boss Brendan Rodgers instructed Martin Skrtel to deliberately rough him up during a training session. Afterwards, Rodgers informed Morgan that he would be released, as he was physically too weak. The teenager sat in his car and cried.

Recommended story: Football's lost wonderkids

He was also unprepared mentally. After joining then-Championship side Yeovil Town, his career quickly went into free-fall. Now aged 22, he finds himself playing semi-professional football for sixth-tier outfit Halifax Town.

“I’d never lived away from home when I joined Yeovil,” Morgan tells FFT. “The longest I’d been away from Liverpool was for four or five weeks with England. It was really hard and was a shock to the system.

“Mentally I also put a lot of pressure on myself. I had a reputation for scoring goals, and I thought if I didn’t score 20 goals I’d be a failure. My head went and I had to drop down the divisions to reassess things.”

Morgan probably would have seen some benefit in receiving the same dose of tough love former Manchester United chief Sir Alex Ferguson used to administer to the likes of David Beckham, Paul Scholes and Ryan Giggs during their teenage years.

“Sir Alex would walk into the dressing room at half-time during a reserve team game and point at one of the players,” reveals United’s former youth team coach Paul McGuinness. “He’d say ‘you’ll never play for this club again if you don’t improve in the second half.’” It was his way of testing them mentally.”

Recommended stories: Are academies failing young players?

However, football dressing rooms are different places to what they were in the 1990s. “They’re anti-social environments,” Cadamarteri says. “Players play on iPads and send texts rather than talking, which means they don’t learn communication and leadership skills. You need these to deal with adversity.”

Footballers are also more complex personalities. “Players are softer now, we’re not producing players who shout at each other anymore,” Republic of Ireland striker Robbie Keane tells FFT. “Players go into their shell if they’re shouted at, but you have to be able to handle criticism.”

John Bostock is another bright young thing whose mental fragility saw his career veer off the tracks. The midfielder was the golden boy of English football when he made his senior debut for Crystal Palace in 2007 at the age of just 15.

A year later, he signed a five-year deal with Tottenham, where he joined a host of Europe’s brightest young talents, including Gareth Bale and Luka Modric, at White Hart Lane. But while they shone, Bostock’s progress stalled.

“I wasn’t playing regularly, so when I did get a chance I felt that my every move was being judged,” he reveals to FFT. “I just became very obsessive. I thought if I made one mistake I’d get dropped. I was overthinking everything.”

Bostock was released by Spurs in 2013 after loan spells at five different clubs. His five years at Spurs brought zero starts and four substitute appearances – three of them in the Uefa Cup; one coming late in an FA Cup victory over Cheltenham.

Recommended story: Ashley Cole: Mental toughness

He sought refuge in Belgium, where he began to rebuild his career with Royal Antwerp and second division side OH Leuven, before moving to France to join Ligue 2 side RC Lens this summer. He says that leaving England gave him a chance to reflect.

“I’ve driven myself crazy, thinking about why things went wrong,” he adds. “The biggest battle for a footballer is dealing with failure and not fulfilling your own expectations. In hindsight I wasn’t mentally prepared to handle everything.”

The 24-year-old has been painted as one of football’s lost boys, an infamous group of players who failed to fulfill their potential after being paid far too much too young. Crucially, however, his story doesn’t fit that narrative.

“I became a Christian at 16, I didn’t go to nightclubs and I’ve never touched alcohol,” he says. “I knew players who did but then they did the business on the pitch, too. I slept and ate perfectly; I made sure that nothing was out of place because I didn’t want to look back and have any regrets.

“But the mind is so powerful. I became scared to fail and make mistakes. On the pitch you want to operate without thinking. Elite athletes need to be able to relax in high-pressure moments – that’s what separates the great players from the rest.”

Tottenham’s Dele Alli was 16 when he made his professional debut for MK Dons. So why was he able to succeed where Bostock failed? A 2012 study - ‘Why Talent Needs Trauma’ – suggests that early setbacks during childhood can develop mental toughness, which transfers on to the pitch.

Recommended story: Dele Alli: How to play with confidence

Alli’s father, Kenny, left the family for America when he was just one-week old, while his mother, Denise, suffered with alcohol addiction. Aged 13, Alli moved out of the family home to live with the parents of another Dons scholar.

“Dele is quite unique,” MK Dons’ academy director Mike Dove said of him recently. “He had a tough upbringing, but those formative years were important for his resilience. They made him fear-free and nothing worries him on the pitch.”

McGuinness, meanwhile, is a believer of another school of thought. He thinks that players like Bostock and Morgan are products of a youth system which doesn’t allow players to develop their mental strength before they’re exposed to first team football.

“Football sounds like such a great life, but there are so many ups and downs,” he says. “You need to have the ability to stay level, so you don’t get too high and you don’t get too low. Players have to be subjected to challenges, which replicate the mental stress of first team football.”

Another of Ferguson’s tricks at Old Trafford was to promote players to train with the first team before dropping them back down to the reserves. “That’s the reality of professional football,” adds McGuinness, “it was a dress rehearsal for life in the first team.”

Recommended story: Gary Neville: How to become a master of mentality

But how can clubs prepare players to deal with the pressure of performing in front of large crowds and avoid freezing in the manner in which England players appeared to do at Euro 2016?

“Academy players need to play more knockout football from a young age,” he continues. “In tournament football, such as the FA Youth Cup, players get used to playing under the pressure of performing and making mistakes in front of big crowds.

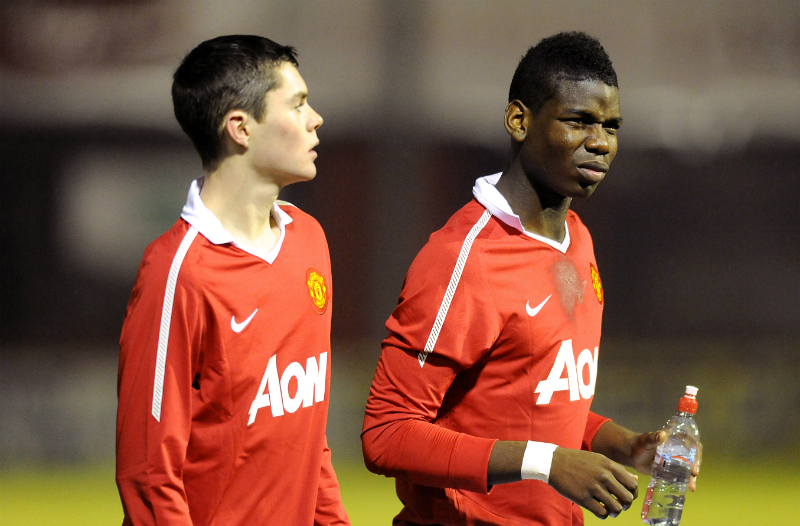

“The youth team Paul Pogba played in won the Youth Cup in 2011. He played in front of 35,000 people in that final. He became used to performing under stressful conditions. We could see players develop mental toughness as they progressed through tournaments.”

McGuinness also cites mental rehearsal as a key tool. “We used to say to Marcus Rashford ‘Don’t let it be a surprise when you play in the first team.’ It got him used to dealing with a level of expectancy from us, but from a young age in his head it also became a case of when rather than if.”

A perceived lack of mental toughness isn’t a problem exclusive to English shores. Former Manchester United scout Tom Vernon is the chairman of Danish club FC Nordsjaelland and the owner of Ghanaian football academy, Right To Dream.

Recommended story: Character team building

“I set up the academy 16 years ago and found that there was a lot of technical quality, but often a lack of character,” he says to FFT. “A lot of players came from very poor backgrounds, but many still lacked mental resilience. We thought we could gain a huge advantage if we found a way to develop character.”

Vernon developed an eight-year curriculum and appointed a head of character development to oversee the project. From the age of 10, players are educated on all areas of character that help them to perform better.

“We’ve built our curriculum around a core literature of 70 books,” he continues. “Mindset by Carol Dweck is really important for us and the Chimp Paradox is another. We go through all this and make it football specific. Our coaches also attend book clubs – they want to understand how to make players dig deeper.”

Vernon was quick to replicate that model in Denmark when he took the helm at Nordsjaelland in December 2015, where experiential learning is also key to players’ education. “We take the players to Africa from the age of 13 and they see how to operate and survive in a third world country,” he explains. “Players used to clean senior players’ boots, but this is our way of taking them out of their comfort zone and exposing them to uncomfortable environments. If they learn to deal with this, they’ll be mentally tougher out on the pitch.”

Every player also designs a feedback project back in Copenhagen, with the aim of keeping them in touch with reality. “A lot of the boys are working with the homeless. They realise what a privileged position they’re in. We firmly believe in developing the whole person.”

Recommended story: Six tips for developing leadership

The project is in its infancy in Denmark, but Vernon believes it is already paying off at his Ghanaian academy. He explains, “They have won the Milk Cup; they’re the world champions of the Nike Premier Cup – the elite under-15 tournament in world football. They also won the Gothia Cup, which is the largest international youth tournament in the world, that involves 1600 teams from 80 countries.

“We think part of that performance is down to the collective character of the group we’ve developed. We think we ask our players to dig deeper on the back of the education we’ve given them. When they face adversity they don’t complain -they keep pushing.”

FFT is struggling to imagine a Premier League academy player wearing a pair of Beats headphones while reading the Chimp Paradox or dishing out bowls of hot soup to the homeless. But Vernon says it’s high time European clubs start to embrace new methods.

“Clubs provide players with absolutely everything, partly because there’s so much competition for talent,” he says. “But I don’t think that’s a good thing because it doesn’t inspire a player to chase something.

“Clubs have got such big budgets now, why not take them to Eastern Europe, Africa or South America and make it a little bit more uncomfortable for them? We invited several Premier League clubs to Africa to see what we’re doing, but they told us what we do wouldn’t get past their health and safety checks.”

Perhaps those clubs will pack their young players off to the Lake District to tackle an old-fashioned cross-country run. Or not.