Is this the most intelligent club in England?

FFT visits Southampton to find out how the club are educating their next generation to be as intelligent in the classroom as they are on the pitch

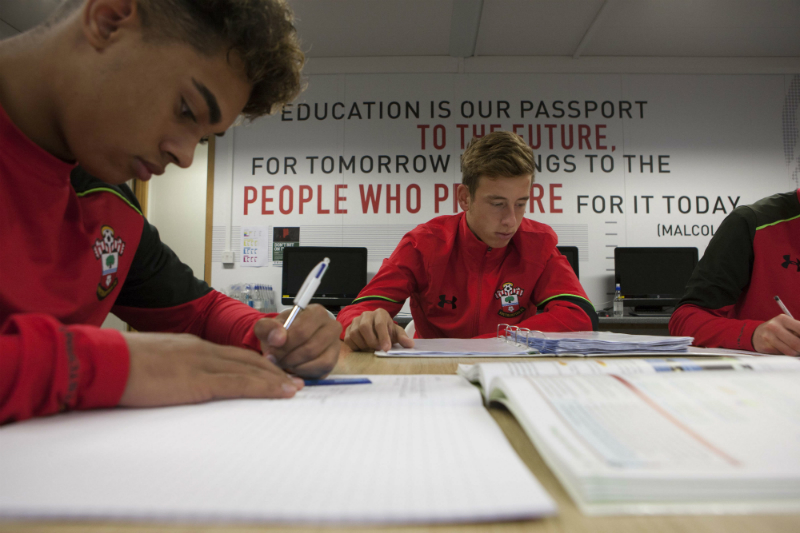

A classroom inside a grey portakabin at Southampton’s Staplewood training ground provides a glimpse of the future and a window into the past.

Luke Shaw, Calum Chambers and James Ward-Prowse studied for their GCSEs inside these four walls, while daydreaming of football stardom. They were educated the ‘Southampton Way’ – a motto coined by the club to sum up their commitment to football and academic education.

It’s more than just empty rhetoric. Chambers left school with nine GCSEs, but it’s Ward-Prowse who remains the poster boy of the Saints’ philosophy. He made his first team debut aged 16 and achieved a distinction in a BTEC qualification two years later, which could’ve seen him go on to study at a top university.

Ward-Prowse is a prototype of the intelligent footballer Southampton are trying to produce through their own unique brand of football schooling.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“We want bright and intelligent players coming through our system, Saints academy director Matt Hale tells FFT.

“Football is a game which requires players to solve problems quickly. If a boy is studying maths, he has to problem solve. If he gets better at doing that in the classroom, we believe he’ll be better at doing it on the pitch.”

Southampton’s philosophy is underpinned by 10 commandments, written in white lettering on red signs pinned to various walls in corridors, offices and classrooms around the complex. They serve as a constant reminder to academy players of the conduct demanded by the club once they’ve enrolled at the Eton of football academies.

Sadly, FFT has already broken the first rule, which states all players should have their shirts tucked in and socks pulled up at all times.

“As a group of staff we wanted to put the ‘Southampton Way’ down on paper,” says Hale. “What do we expect of players? What’s our coaching and teaching style?

“When a player joins the academy, we sit down with him and his parents and go through the 10 commandments. This way everyone knows what our expectations are on and off the pitch.

“One of the rules we brought in this season is that they’re not allowed to wear coloured boots until they get a professional contract. That’s just part of our culture.”

Education even plays a role in the recruitment of young players, with the club requesting character references from schools to pinpoint any behavioural concerns.

Hale adds: “If we bring a boy in as a teenager then we need to know if he’s got the right mindset to train several times a week and balance that with his studies.

“A bad reference wouldn’t stop us from bringing someone in but it would give us an idea of a player’s weaknesses and where we need to work with them.”

Most players enter the academy at the foundation phase - between the age of nine and 12 – and train with the club once a week on day release from their schools.

Training means they miss an afternoon of study, but they make up for it with two hours worth of lessons with the Saints’ academy teachers to make sure they don’t fall behind with their work.

“Everything we teach them is related to football,” says the club’s primary co-ordinator Kevin Batchelor. “All their subjects have a football emphasis to help them see the link between school and football from a young age.

“The under-9s write a player profile about themselves with information about their families, friends and schools. We pass it on to their coach so he has more information about each individual.”

As a Category One Premier League academy, Southampton are expected to monitor the trajectory of their players’ school grades once they begin to undergo schooling at the club.

“The demands are pretty rigorous,” says Hale. “We have to upload their grades on to a software programme so the Premier League can audit that at any time.

“If a player comes to us and his grades start dropping off, you have to show them that you’re addressing it immediately before it escalates into something major.”

If a player isn’t pulling his weight then Southampton have a simple punishment equivalent to a school detention to ensure unruly schoolboys quickly fall back in line.

“Some players think education is optional,” explains academy education teacher Mark Gardner. “We say, if you don’t do your work, you don’t play and the coaches reinforce that so it always works.”

Education manager Toby Redwood adds: “The only time I’ve ever had a problem is with lads who have come in from other clubs at an older age. They haven’t been brought up with our standards. Education hasn’t been important elsewhere.”

Not all of the boys are gifted students. Shaw, who was nicknamed ‘the dopey one’ by classmates Chambers and Ward-Prowse, was a particularly testing case. Joe Says, another of the academy’s on-site teachers, breaks into a laugh as she remembers working with the left-back when he was a teenager.

“Luke was a lovely lad, but he wasn’t very academic. He was the type of boy who just wanted to play football and do P.E. every day.

“We had to work very hard with him to show him that school was important so he had something to fall back on it if he didn’t make it.”

It’s this dose of realism that also explains Southampton’s emphasis on education. Saints players are routinely reminded that few of them will go on to become professionals.

“It’s a tough industry and a tough business,” Hale acknowledges. “We work very hard to make sure the boys who don’t make it have alternative career paths. We feel we have a duty to do so.

“We have great links with several US universities and we invite them over to do a presentation to our boys once a year. Many of them have gone on to study over there.”

The Saints’ curriculum has a unique twist. The club’s psychology department is using neuroscience to educate and improve the performance of their players’ brains.

“We’re looking at the different areas of the brain we can tap into which will have an impact on the pitch,” explains academy psychologist Amy Spence. “One of these is decision making. This is controlled by one specific part of the brain and we tell the boys we can train it like they do their muscles in the gym.”

Players from the age of nine use a piece of technology called the Neurotracker, which requires them to track four balls amongst a moving pack of eight for 10 seconds. Heart rate variability training teaches youngsters how to control their breathing and deal with stressful situations by using a monitor, which measures the time gap between each heartbeat.

The Fitlight reaction-training device is another tool used regularly, which tests the ability of academy players to react to a sequence of discs, which light up at random.

It’s even become popular with the first team. Fraser Forster used the Neurotracker and fitlights during his recovery from a broken kneecap to hone his cognitive skills.

The gadgets sound like fun, but they serve a serious purpose. They’re used as part of batch of in house psychological tests carried out three times a year to provide a baseline measurement of a player’s mental skills.

Every 12 weeks, psychological reviews are also carried out with players from the under-nine age group and upward, focusing on leadership, confidence and behaviour. Parents are even invited to attend.

The continuous raft of tests and daily monitoring place intense pressure on academy players as they balance their football and academic education.

“We had a player come and visit us about anxiety, he was really struggling to deal with pressure and it was showing on the pitch,” reveals Spence.

“We monitored his mood at certain times every day for several weeks to see if there was a trend. We met with the player and his coach twice a week for six weeks to help him and track his progression.

“In week one his body language on the pitch was visibly not good, he drifted out of the game after making a mistake. By week six he’d learnt to forget about mistakes and get straight back into the game.”

The individual nature of Southampton’s education programme is designed to develop well-rounded human beings with the personal qualities to deal with the challenges life will inevitably throw at them.

Hale explains how self-discipline is drilled into players from a young age. “If one of our boys is going to be late for training or a game – even if he’s 11 or 12 - he has to make the call to the coach – not mum or dad - because they won’t always be there.”

It’s a relevant point as players enter their teenage years. Those who live a distance from Southampton are encouraged to stay with a host family once a week between the ages of 13-15. In their final year of school, this can increase to three nights.

Though most of their academy players are recruited from the surrounding area, five players have been brought in from London and now live full-time with host families and study at the Saints’ partner school, Applemore College.

“As a category one academy, we’re allowed to recruit players from any area of the country from the age of 12,” Hale explains. “But we have to move them to a partner school and house them within a travelling distance of the academy. We have 46 host families in the area and they’re visited by one of our two welfare officers every six weeks. They will address any issues such as diet, or whether the player is socialising with the family.”

The Saints teaching staff provide a life skills programme so players are capable of looking after themselves while they live away from family and friends.

Cookery classes teach the boys how to make meals in preparation for moving into their own apartment – something the club strongly encourages if they sign professional terms at 16.

A booklet is also given to all players between the age of nine and 23 telling them how to iron a shirt or even find a fuse box at home. Mechanics visit the club to teach basic car maintenance skills and orienteering sessions around Southampton are designed to develop communication skills.

Says sympathises with the challenges the teenage boys face: “They’re tired a lot more than other boys their age. They have to deal with schoolwork, training, moving out and the pressure of wanting to succeed, particularly in the GCSE year.

“Some of the lads who are from London or the West Country don’t get to see their parents, friends and girlfriends very often and they can get lonely. They have a lot more on their plate than other boys their age.

Like many boys at secondary schools across the country, not all of them will graduate with flying colours and win a professional contract, but the club are confident they already have their next batch of intelligent footballers.

“We have a lot of boys above average,” beams Says. They’ve seen how successful Ward-Prowse, Chambers and Shaw have been in football and academically and that’s set the tone because they’ve become role models for the younger boys.”

Goalkeeper Alex Coles achieved seven A* and two As at GCSE level, as well as representing England’s Under-16s. This year he will begin a BTEC qualification. Oliver Cook – a centre-back who plays for the club’s under-21 side – is keen to begin studying an English A-Level at the academy alongside full-time training.

For the teachers at Southampton, the hard work goes on. They soon hope to introduce a mentor programme, which will see every age group assigned a first team player who will watch their games and offer advice and guidance.

A young captain’s leadership programme is also in the works. Coaching and teaching will work with youngsters to develop personalities who will assume responsibility on the pitch from a young age.

For now, though, Ward-Prowse remains Southampton’s star pupil. He recently delivered a talk to academy players about his journey at the club and the importance of his education.

His story is helping to battle a culture embedded within football. Says has the final word: “There’s a stereotype that footballers aren’t academic, but we’ve proven that’s not the case. You can be successful in the classroom and on the pitch.”