Non-league to Premier League: How on earth does it happen?

In an era of mega-bucks TV deals and huge international scouting networks, many players still rise from semi-pro football to the domestic game’s summit. FFT investigates how it remains a path well trodden

Troy Deeney was drunk. And yet, this would be the day. He didn’t know it at the time, and he certainly wasn’t prepared for it, but this would be the day his rise to the Premier League began.

Deeney was playing for Chelmsley Town, his local non-league side in the West Midlands. It was just another match – until the weather intervened. The game that Walsall scout Mick Halsall was planning to go and watch that day was postponed, so instead he went to see his son’s team take on Chelmsley.

Despite taking to the field in a state of inebriation, Deeney scored seven goals that afternoon in an 11-4 victory. Halsall immediately offered the 17-year-old a trial – a trial that he still had to be dragged out of bed to attend – and the rest is history. A decade later, the striker is the captain of Premier League club Watford, and so valuable to the Hornets that they reportedly rejected a £25 million bid for his services from reigning champions Leicester last summer.

In a time when the financial gulf between the Premier League and the rest is ever-widening, making it from non-league to the top flight seems improbable. It goes against everything the academy system has been set up to achieve. Yet it still happens, and with surprising regularity.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

When Sam Allardyce named his first England squad at the end of August, four of the players he selected had risen from non-league. Jamie Vardy, Chris Smalling and Joe Hart, who made his senior debut in the Conference with Shrewsbury Town, were joined in the group by West Ham’s Michail Antonio, formerly of Tooting & Mitcham United.

“I know loads of people who don’t appreciate being a footballer,” Antonio tells FFT. “I appreciate every single moment of it. I didn’t go through an academy, but I had the self-belief that I should be a pro footballer. Now I’m here, no one’s telling me I’m not good enough.”

Antonio had been part of Fulham’s Football in the Community scheme as a youngster, but was never signed up. Almost all of those players who’ve gone from non-league to the top have a rejection story. Often, you sense that it's as important as the journey itself.

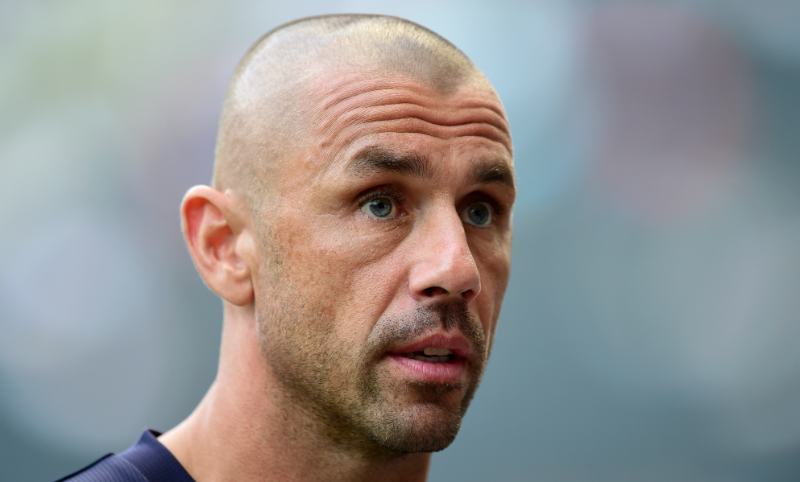

“I was an apprentice at Southampton but I was released,” Kevin Phillips explains to FFT. “It was a big heartbreak. I wrote to virtually every club in the country, asking for a trial. I only got three responses, all of them negative. You almost feel then that your chance has gone.

“I had to go out into the big wide world, into non-league, but I kept plugging away. I tried to be as disciplined as I possibly could, staying in on a Friday night when my mates were going out. It’s difficult when they’re knocking on your door, saying: ‘You’ve had your chance in football – come on, let’s go out’. But although I only had a non-league game the next day, I still believed that someone would be there watching and would give me an opportunity.”

Phillips had been told by Southampton that he was too small to be a striker, and he began his non-league career as a right-back. Moving into adult football with Baldock Town was a challenge, but it was the making of him.

Others have learned from the more physical nature of the semi-pro game as well, even if they didn’t always appreciate it at the time. Everton winger Yannick Bolasie tells a story of a Rushden & Diamonds game at Altrincham in which he tore the opposition to shreds but had to be substituted at half-time for his own safety, as Altrincham had become so irritated that they resorted to kicking lumps out of him. It’s a tale that sounds familiar to Antonio.

“I played against men from an earlier age than academy players do,” says the West Ham man. “I remember one game, when I was 16: I was the quickest on the pitch, I was running down the left and there were three tackles where I had to do hurdles. They didn’t go for the ball – they went for my ankles. I managed to cross the ball, we scored, and after that someone stood on my toe. They aren’t nice in non-league, but it makes you stronger.”

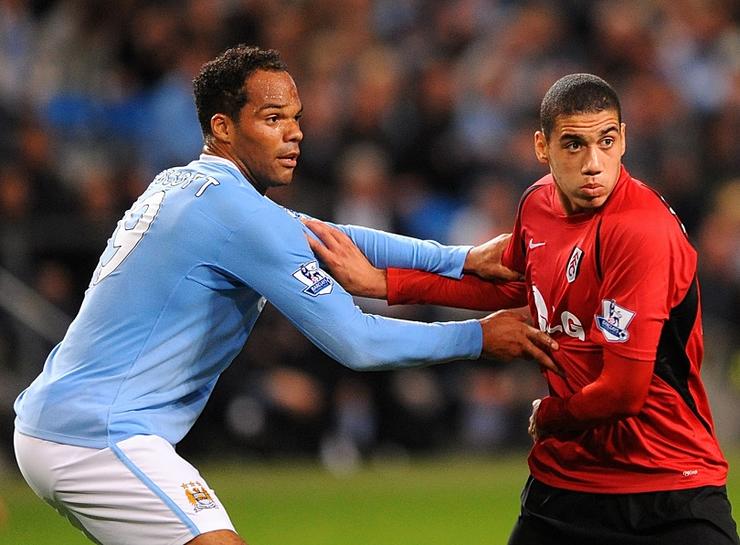

For Smalling, a sudden increase in strength surprised everybody at Maidstone United, where he progressed from the youth team to the first XI after leaving Millwall’s academy.

“My first memory of him was in a Kent Cup game,” recalls Smalling’s former Maidstone boss, Lloyd Hume. “He was a tall and gangly player who clearly had talent, but there were a couple of other players in that youth team who looked stronger and perhaps more ready. When he came back for pre-season, though, he’d gone in one summer from being a spindly boy to being a man. We did a bleep test and it got to the stage where we had to stop it because he was on his own for some time.”

Smalling was still at school during his Maidstone days. Fellow non-league graduate Duncan Watmore combined his own duties at Altrincham with life as a student, continuing his course even after joining Sunderland and gaining a first-class honours degree in economics and business management.

Others had to find jobs. Charlie Austin was a bricklayer, George Boyd worked in a sweet shop, Ashley Williams helped on the hoopla stall at Drayton Manor Theme Park and Craig Dawson collected glasses down at the Dog & Partridge pub, where he was persuaded to join Radcliffe Borough by the club’s chairman, son of comedian Bernard Manning. Kevin Phillips remembers those days well.

“I was working 12-hour shifts in a warehouse,” he tells FFT. “It was tough, but it was what you had to do. I remember my first day as a signed professional for Watford: we didn’t have to start until 10.30am, which I couldn’t believe, because normally I’d already done about three or four hours’ work by then. Then when we finished at 12 or 12.30, the lads started walking off the training ground and I said to them, ‘Is that it? Are we finished?’ They said, ‘Yes, you’re free to go home now’.

"I couldn’t believe it – I was used to having another eight or nine hours’ work left! It was surreal, but it was also a fantastic feeling. My theory now is this: when players come into an academy, why not send them off to a warehouse and let them work a 12-hour shift – like kids who do work experience at school – just so they can see how lucky they are if they become a professional?”

Phillips, now assistant coach at Derby, turned professional at 21. Examples in the mould of Tony Book, who left non-league aged 30 and captained Manchester City to the First Division title four years later, are much rarer. Book’s age was such a concern that Malcolm Allison, who brought him into the Football League at Plymouth before enticing him to Maine Road, told the defender to doctor his birth certificate to convince the Pilgrims’ chairman he was 28.

Rising through the leagues brings fame and (relative) fortune, and the pitfalls associated with both. Deeney recalls how he partied excessively following a significant pay rise upon joining Watford. Eventually he was involved in a brawl outside a nightclub that resulted in two-and-a-half months in prison.

Few people paid any attention when Andre Gray posted abhorrent homophobia on Twitter during his time with Hinckley United, but the same tweets became headline news when they were dug up within minutes of his first Premier League goal for Burnley. Gray has stressed that he’s a changed man since he broadcast those views in 2012. The path from non-league to the Premier League cannot be trodden without a willingness to learn – a quality that Smalling always had at Maidstone.

“Chris isn’t Rio Ferdinand on the ball, but at non-league level he was,” says Hume. “He was casual and confident. But there was one game when he got kicked and we nearly conceded, and he got a rollicking from me at half-time. I was trying to explain, in no uncertain terms, that there are times when you’ve just got to put your foot through it. But you only had to tell Chris once. He was always willing to take on board anything that anybody said to him.”

Smalling’s career path is very unusual in that he jumped straight from the Isthmian League to the Premier League, moving from Maidstone to Fulham. Hume says that Chelsea looked at him, too, but didn’t offer the defender a long-term contract because they were convinced they already had the next big thing in Michael Mancienne (now at Nottingham Forest).

Most players progress step by step. For example, 25-year-old midfielder Sam Clucas entered the Premier League this term having played in the Championship with Hull last season, in League One with Chesterfield the year before that, in League Two with Mansfield the year before that, and in the Conference with Hereford in 2012/13.

Clucas, like Derby’s ex-Watford wing-back Ikechi Anya, went from non-league to the top flight after spending some time with the Glenn Hoddle Academy in Spain, which was set up to provide a second chance to players released as youngsters. Clucas had been on Leicester’s books before he was cleaning tables in a Debenhams café.

Phillips says that the hard times make one’s days in the top tier all the sweeter, particularly as he won the European Golden Shoe in his first year in the Premier League, netting 30 times for Sunderland.

“It was only four-and-a-bit years from working in a warehouse to playing my first Premier League game,” adds the 43-year-old. “I’m immensely proud to have been awarded the Golden Boot, coming from non-league – and I’m still the only English player to have won it. When I see Jamie Vardy, I know what he’s experiencing. I know how great it feels.”

Phillips was Vardy’s team-mate at Leicester when the Foxes were promoted to the Premier League, before working as the club’s assistant coach in their first season back in the top flight.

“How was he to deal with? Sometimes it was a nightmare!” Phillips laughs. “Jamie’s a lively character and he’s never short of a word or two. He’s full of life, but that makes it easier for you, as you don’t have to gee him up and get him going. The hunger is there.

“People tell me that when he first signed from Fleetwood, he found it difficult to settle and had one or two issues off the field. When you come from non-league now, the spotlight is more intense than when I came through. But I think he has learned an awful lot.”

That element of non-league rawness Vardy still possesses is something Antonio has, too. The winger believes it gives him an edge.

“My style of play is different to how a lot of people in academies play,” he says. “No one runs at players like I do, or gets to the back stick and then overpowers a defender. There’s a wealth of talent at non-league level. I know players who didn’t make it and I can’t believe that they didn’t. They had ability that could have easily been coached into something. You just have to be willing to take the risk.”

Dario Gradi, a man renowned for unearthing some of England’s finest talents during his 33 years with Crewe, agrees. “There’s probably a lot of decent lads in non-league now,” he tells FFT, “because the number of foreigners means that the English boys are getting pushed further down the system. We tried to sign Vardy from Halifax, but they wanted £100,000.” In hindsight, Crewe presumably wish they’d paid it.

“It’s going to be a really interesting situation now, with Brexit,” muses agent Jon Smith, who represented Jermaine Beckford on his rise from Wealdstone to Everton. “Are teams going to give more young English players a chance, or will they still buy from abroad? Clubs are looking for players who have the right profile and mental attributes, and sometimes guys in the lower leagues fit the bill.”

The academy system should have spelt the end for non-league players making it to the very top of the game. Instead, it’s one of the biggest reasons why they continue to do so.

“If you go and watch an under-23 match, it’s almost a game of keep-ball,” explains Lloyd Hume. “But when you’re playing down in non-league, every game really counts. You watch Vardy playing: he runs around as if it’s the first match he’s ever played, because that’s how he has been taught to play. With other players who have come through the system, if things don’t go their way then their head drops and they think ‘woe is me’.”

Phillips adds: “You look at the academy system now and players aren’t allowed to clean boots and clean the stands, the toilets and showers like we used to – but all of that gives you a good grounding. The big argument now is whether the under 23-league is really that competitive. When these boys are asked to step up to the first team, are they properly prepared? If you sign someone from non-league, however, you’re getting a player who’s already played men’s football.

“I would like to see more players coming from non-league. There are some out there who can make the jump. They just need an opportunity.”

An opportunity such as the one Troy Deeney was given 10 years ago. Imagine how many goals he’d have scored that day if he’d been sober.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2016 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Chris joined FourFourTwo in 2015 and has reported from 20 countries, in places as varied as Jerusalem and the Arctic Circle. He's interviewed Pele, Zlatan and Santa Claus (it's a long story), as well as covering the World Cup, Euro 2020 and the Clasico. He previously spent 10 years as a newspaper journalist, and completed the 92 in 2017.