How Johan Cruyff reinvented modern football at Barcelona

Four years on from his passing, we look at the enduring legacy Johan Cruyff left at the Nou Camp – and what it means for football worldwide today

“Johan Cruyff painted the chapel, and Barcelona coaches since merely restore or improve it” – Pep Guardiola

It’s 7pm on April 28, 1988. The Hesperia hotel on the Carrer dels Vergos, a tight street to the north of Barcelona city centre and five minutes by car from the Nou Camp, is abuzz.

Twenty-one Barça players, plus head coach Luis Aragones, sit behind a conference table in a plush meeting room. “President Josep Lluis Nunez has deceived us as people and humiliated us as professionals,” reads square-shouldered captain Alexanko from a statement. “In conclusion, although this request is usually the preserve of the club’s members, the squad suggest the immediate resignation of the president.”

The declaration is as shocking as it is unprecedented. “Nunez doesn’t feel the colours of this club, nor does he love the fans,” adds midfielder Victor Munoz. “He only loves himself.” The club is openly at war. With itself. Over money. The Spanish treasury is investigating every Blaugrana contract, believing tax to be owed because each squad member must have separate playing deals and image rights agreements. When club officials insist the players make up the difference to the taxman, the squad demand president Nunez’s head.

The so-called Hesperia Mutiny is the lowest point in what has been Barcelona’s worst season since 1941/42. Coach Aragones is suffering with depression and will leave at the campaign’s end. Barcelona have gone from European Cup finalists in 1986 to a laughing stock in just two years. To turn things around, and ensure his re-election in June’s upcoming presidential vote, Nunez plays the one card available to him.

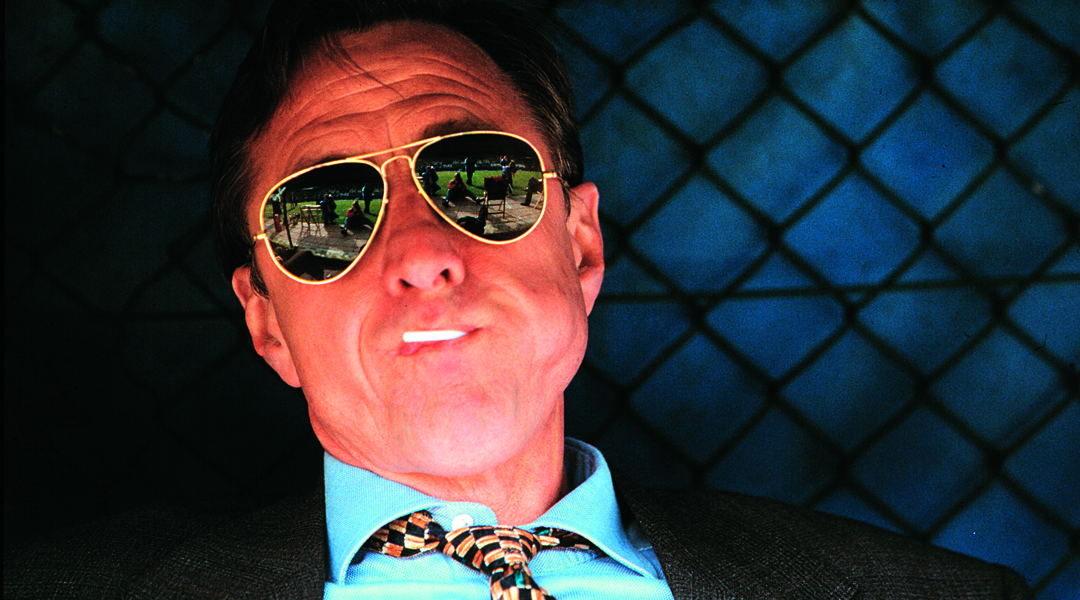

Six days later, on May 4, 1988, Johan Cruyff is announced as Barcelona coach. Los Cules had won one league title in 14 years. By the time the board sacked the Dutchman – amid much acrimony – eight years later, Barça had won 11 trophies. The greatest Total Footballer of his generation had saved the club on the pitch in the late 1970s; a decade later, he did it again from the dugout. Many Barça fans still believe the side he built, the Dream Team, is their best ever. All those years after he began that first season in the Nou Camp dugout, FFT reveals the inside story of how his passion for beautiful football, sometimes cantankerous character and will to win made today’s Barça great. You know La Masia? That’s pretty much his gig...

“A kid of 23, my doors were opened to the sky”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Cruyff’s post-Hesperia rebuilding job began immediately. Fifteen players were sold, including first-team favourites – and principal mutineers – Victor Munoz, Ramon Caldere and Bernd Schuster, the latter to Real Madrid. In their place came 12 additions, of whom winger Txiki Begiristain, attacking midfielder Jose Mari Bakero, centre-forward Julio Salinas and defensive midfielder Eusebio became crucial cogs in Cruyff’s future Dream Team. “I was proud that a player of such worldwide standing was interested in me,” Eusebio tells FFT. “His years as a player at the Nou Camp changed Spanish football and Barcelonismo. I was a kid of 23, and my doors were opened to the sky. He brought through a group of young, hungry players who weren’t weighed down by the club’s recent unstable history.”

Much to Nunez’s chagrin, Cruyff retained chief mutineer Alexanko, despite the 32-year-old being booed by a packed Nou Camp at the squad’s pre-season unveiling. “Alexanko did nothing except what was his duty as captain,” Cruyff huffed. “He was the spokesman – he didn’t let his players down. That’s character. The messenger often gets killed. Not with me. Although not a regular, he’s a leader, and there was a unity.” The inference was obvious. To hell with you, Mr President, I’m the boss here. The ‘hands-on’ approach with which Nunez ran the club, in a similar fashion to his construction and hotel businesses, would also end. “If you want to talk to me,” Cruyff told the president, “I’ll come to your office. You don’t come to my dressing room.” Cruyff’s and Nunez’s marriage was always destined to be one of convenience.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2013 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe today! 5 issues for £5

Next came stylistic restructuring. Gathering his newly assembled squad for a first-team meeting in early July 1988, El Flaco (‘the skinny one’) outlined the system he wanted to employ.

“He got a blackboard and drew three defenders, four midfielders, two out-and-out wingers and a centre-forward,” recalls Eusebio. “We looked at each other and said: ‘What the hell is this?!’ This was the era of 4-4-2 or 3-5-2. We couldn’t believe how many attackers were in the team, and how few defenders. He single-handedly introduced a new way of playing football in Spain. It was a revolution.” The 3-4-3 – adapted from the 4-3-3 Cruyff played under Rinus Michels for Ajax and Holland in the 1970s – was born.

“If you have four men defending two strikers, you only have six against eight in the middle of the field: there’s no way you can win that battle. We had to put a defender further forward,” Cruyff later explained.

“I was criticised for playing three at the back, but that’s the most idiotic thing I’ve ever heard. What we needed was to fill the middle of the pitch with players where we needed it most. I much prefer to win 5-4 than 1-0.” Indeed, defensive thinking didn’t enter Cruyff’s mind. At one point keeper Andoni Zubizarreta asked his coach how he wanted the team to defend a set-piece. “How should I know?” came the curt reply. “You decide. You’re more interested in how to defend a corner than me.”

Further forward, the players revelled in the system’s freedom. “I loved the 3-4-3,” recalls Eusebio, who went on to make more than 250 appearances under Cruyff. “I struggled in other systems more than at Barcelona.

“My technique, vision and intelligence to move the ball quickly fitted perfectly with his Barça, whereas elsewhere it wasn’t enough just to pass and keep play moving. As a central midfielder, I was always involved and had options, especially from the nominally wide midfielders, who Johan wanted very narrow.”

At the formation’s heart was the supremacy of possession that remains Barca’s trademark. “It’s a basic concept: when you dominate the ball, you move well,” Cruyff said. “You have what the opposition don’t, and therefore they can’t score. The person that moves decides where the ball goes, and if you move well, you can change opponents’ pressure into your advantage. The ball goes where you want it.”

“Without Cruyff, the Xavis and Iniestas of this world wouldn’t exist”

But there was a problem. Cruyff’s squad was thin on the highly technical artists needed to implement his shift to a cerebral style. A possession-hungry production line was needed. La Masia had to be overhauled.

Incredibly for a club that has gone on to produce Xavi, Iniesta and Messi, they selected players not on ability, but potential physique. In 1986, one 15-year-old undertook his prueba de la muneca, or ‘doll’s trial’, whereby only those who would grow up to measure 1.80m (5ft 9in) would be kept on. “I’ll be taller than 1.80m,” he screamed. “I’m going to be a professional footballer.” His name? Pep Guardiola.

Cruyff’s arrival sparked the change. “I had short lads like Albert Ferrer, Sergi or Guillermo Amor; players without great physiques but who pampered the ball with their touch and pressed the opposition like rats,” he recalled. “Even Pep wasn’t all that physically, but with the ball he was intelligent. That’s what I wanted.”

“For Johan it was more about staying tight, being quick and trying to go forward than being good in the air,” right-back Ferrer, who went on to play for Chelsea, tells FFT. “He clearly knew what kind of players he needed, and he had no problem in selecting shorter players or bringing through youngsters. He was convinced that this was the way forward.”

Every team, from the under-8s to Barça B, aped the senior side’s revolutionary 3-4-3 and desire to keep the ball. The production line Cruyff craved had arrived. La Masia graduates Ferrer, Amor and Sergi amassed more than 1,000 first-team appearances between them. None was above the 1.80m cut-off. Taller, but still slightly built, Guardiola played 384 times.

“The ball was converted into the only protagonist and even fitness work was done with a football,” recalls Mundo Deportivo journalist Oriol Domenech, who spent six years in Barça’s youth teams in the Cruyff era. “There were more opportunities for the little players like me. When I was at La Masia, Guardiola was very thin and it was Cruyff who said that he always had to play because eventually he would grow. Without him, the Xavis, Iniestas and Thiagos of this world wouldn’t exist.”

“If I wanted you to understand, I would have explained it better”

Cruyff’s basic Barça blueprint was in shape, but there were teething problems, despite winning the 1988/89 European Cup Winners’ Cup and the Copa del Rey a season later. Summer 1989’s marquee signings Michael Laudrup and Ronald Koeman failed to shine. Koeman, in particular, had an underwhelming first campaign and Cruyff became weary of defending his compatriot to the press pack.

Daily briefings were abandoned – “talking to the press is dangerous” – as the me-against-the-world mistrust in Cruyff’s character came to the fore. He did interviews, but their content became increasingly cryptic: “If I wanted you to understand, I would have explained it better,” he told one reporter.

Finishing 11 points behind Real Madrid, Cruyff was only saved by winning the 1990 Copa del Rey. Indeed, Nunez vetoed a vote of no confidence from Barca members to sack the Dutchman in the close season.

Yet 1990/91 would be the season the legend of Cruyff and Barca truly began. La Masia’s fruits were being harvested, even if Cruyff’s thinking in blooding youth teamers was partly motivated by self-preservation.

“I was here under the Franco dictatorship: I understand how Catalan people think, I know the character,” he explained. “Barça fans like seeing players from the cantera in the first team – it makes them feel that the coach somehow is more a part of Barcelona. I tried to produce a game that they could claim as Catalan. That way, the fans are less likely to whistle if things go wrong.”

Temperamental, but lethal in front of goal, Hristo Stoichkov proved the missing piece of the jigsaw. A versatile forward who would dribble, pass and shoot from the left with unerring efficacy, the Dagger had what the Spanish call mala leche, ‘bad milk’ meaning a confrontational character that does anything to win.

Such as receiving a two-month ban for stamping on the referee in the 1990 Super Cup Final. When Barça beat Madrid 2-1 to go five points clear in late January 1991, the league looked tied up. Koeman was purring in front of the defence and Laudrup probing from midfield, while Ion Goikoetxea was a Spain regular.

“Cruyff was sucking on Chupa Chups instead of cigarettes”

But Cruyff’s greatest weakness hit with a vengeance. A chain-smoker since his teens, he required a heart bypass to clear a clogged artery, the result of a 20-a-day habit that had only got worse with the stress of the Nou Camp hot seat. That he survived a four-hour operation reinforced his long-standing conviction that God had put him on earth to be the best football player and coach ever.

During Cruyff’s nine-game absence, assistant Charly Rexach won six times to secure the club’s first league title for six years. It was, says midfielder Eusebio, all down to the Dutchman’s training ground work.

“He used to stop every session four or five times and correct our positioning: ‘No, no! Not there. One metre more to the right. Now look: you have a much better angle for the pass. It wasn’t there before’.

These tiny details make you think. They stay with you, and in the end you join the dots between each passage of play. There’s no other coach who could explain that to you, because he was the best in the world as a player. Built up over years they form a huge part of your skills.”

With Cruyff restored to the bench, sucking on Chupa Chups lollipops instead of cigarettes, Barça started 1991/92 slowly. Losing three of their first eight games, the turning point came in November at Kaiserslautern in the European Cup. Despite a 3-1 first-leg victory, los Blaugranas were losing 1-0 at half-time and playing awfully. Motivation was needed.

“Cruyff came into the changing rooms and we were expecting a rocket,” centre-back Miguel Angel Nadal tells FFT. “He just rubbed his hands and said: ‘Bloody hell, lads, it’s f***ing freezing out there.’

"Our season was about to end, and all he did was talk about how cold he was. All the pressure had gone. He was full of self-assurance that the team he had built would triumph, because he’d brought it together. He believed he was always right.”

Cruyff’s men conceded again in the second half, but Jose Mari Bakero’s 89th-minute header secured safe passage. Just as his coach always expected. By May, a second successive Liga was in the bag – thanks to Real Madrid’s unfathomable last-day defeat at minnows Tenerife – with a European Cup final at Wembley against Sampdoria to follow.

“He wanted us to forget the history of the club, and the troubles we had in previous finals like 1986,” recalls Nadal. “He simply said: ‘Salid y disfrutad’ [Go out there and enjoy it]. That took off all the pressure.”

When Koeman lashed home an extra-time free-kick, those words became inexorably linked with Catalonia’s first European Cup. Named after USA’s all-conquering basketball team at that summer’s Barcelona Olympics, the legend of Cruyff’s Dream Team had arrived. Only keeper Zubizarreta and club captain Alexanko were survivors from the Hesperia Mutiny four years earlier.

“There was a different spirit and feeling around the club in 1992 – everyone could feel it,” says Eusebio, immense alongside Guardiola in the final. “We’d spent four years working in one direction, adding the odd new player, to change Barça’s history. We were the chosen ones and knew it was our time.”

All hail the Bloody Hell Team

Though rumours of smouldering discontent between Cruyff and president Nunez refused to ease, especially after a Champions League exit to CSKA Moscow in December 1992, the trophies kept coming. A third successive league title in 1993 – again on the last day, again thanks to a Madrid defeat at Tenerife, again scoring 87 goals – was the highlight. When squat striking genius Romario arrived in the summer of 1993, all was set for a tilt at an unprecedented fourth Liga in a row and second European crown in three years. The Brazilian’s hat-trick in a 5-0 defeat of Real Madrid served notice of the potential upgrade Cruyff had made.

In what became known as the ‘Liga of the Chupa Chups’ after Deportivo La Coruna fans danced a premature jig with giant Cruyff-baiting lollipops on the penultimate day of the season, the 1994 title was achieved only when Depor defender Miroslav Djukic missed a last-minute penalty against Valencia to gift Barça the title.

They had won 28 of 30 available points since losing 6-2 at Zaragoza in February. After that shellacking, Cruyff had promised new deals to every out-of-contract squad member if Barcelona won the league. The press were euphoric, renaming the club the HostiaTeam: the Bloody Hell Team.

Four days later came the planned consecration of the ‘greatest team on the planet’, the Champions League final against AC Milan. Koeman, Guardiola, Romario, Stoichkov: all at the top of their game. The majestic Laudrup couldn’t get on the pitch because of the three foreigners rule. “Barça are the favourites,” crowed Cruyff. “Milan are nothing out of this world. They base their game on defence, we base ours on attack.”

But Milan won. 4-0. Daniele Massaro scored twice, with one each for Marcel Desailly and man-of-the-match playmaker Dejan Savicevic.

Seldom had Barcelona’s defensive malaise been so ruthlessly exploited.

“After four leagues in a row and lifting the trophy in 1992 we probably had too much confidence,” recalls Ferrer. “We thought it would be easy; that if we played to 60 or 70% we’d win.

"It was the beginning of the end. I remember some players were told on the bus straight after the game that they’d be sold. After that final, everything changed.”

“The vice-president threatened to call the police if Cruyff didn't leave”

Going back on his word, Cruyff took a sledgehammer to the Dream Team. Zubizarreta, Laudrup, Goikoetxea and Salinas never played for the club again. Romario left in January 1995 – Cruyff’s parting shot, “He’s not as good as I was. I made others play better; he can only score goals.” By the summer, Eusebio, Stoichkov, Koeman and Begiristain followed. Only Ferrer, Nadal, Bakero and Guardiola remained.

“We had given a lot and he wanted to change things radically,” recalls Eusebio. “As a professional, I accepted that at 31 he might want someone younger to remodel the team, but I believe he could have managed this in a better, less traumatic way.”

Replacements Gheorghe Popescu, Gheorghe Hagi and Robert Prosinecki struggled to make an impact. The goals, once free-flowing, dried up. 4-3 wins turned into 3-2 defeats. Only Luis Figo, bought from Sporting, offered an improvement on the departures. The end, when it came, was as brutal as it was swift.

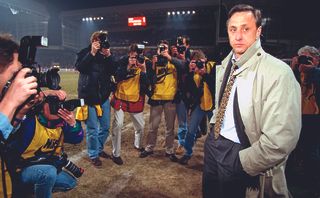

The day before the final home game of 1995/96 – which brought a second year without silverware – against Celta Vigo, the tension between Cruyff and Nunez came to a head amid persistent rumours about Bobby Robson replacing the Dutchman. Vice-president Joan Gaspart went to the dressing room for a chat.

“You Judas,” spat Cruyff in response to Gaspart’s outstretched hand. “How is it possible that Nunez can’t come and do this face to face?” The pair came to blows, the vice-president threatening to call the police if Cruyff did not leave the Nou Camp immediately.

“Looking back on it, it was probably a mistake to go down to the dressing rooms and give him an explanation,” the vice-president later recalled. “It only made the situation worse. Things got violent – we both lost ourselves. We couldn’t carry on after that, not even for two games.” In just 90 seconds, the longest-serving manager in Barcelona history, and at that stage the most successful, was gone. “People like Nunez don’t become chairmen because they like football,” ranted Cruyff, “but because they like themselves.”

A day later, his 22-year-old son Jordi inspired a 3-2 victory from behind against Celta, leaving the Nou Camp pitch to a standing ovation and chants of: “Cruyff, si! Nunez, no!” It wasn’t hard to spot the subtext.

“He reinvented the concept of football in Spain”

Cruyff may be long gone, but, 27 years on from his Nou Camp dugout debut, his footballing legacy endures.

“At the very least, Johan installed our way of playing, an idea of continuity throughout the club,” says Eusebio, who was Barcelona B coach until February 2015. “I could feel his DNA in my team. Every player knew the system already. It penetrated every part of the club. The success of La Masia has proven him right. Every time a youngster reaches that group or the first team, it’s a success that Johan is part of.”

He believes even Cruyff’s greatest defeat serves as an inspiration. “It’s no coincidence that Pep Guardiola was in charge of an incredibly successful generation, because he knows what we were missing in the 1994 Champions League Final: hard work and respecting the opposition. I have no doubt that Pep thought about Milan before any game he was expected to win as Barça coach.”

Espousing possession and restoring La Masia’s importance, it’s fitting that Guardiola overtook his great mentor as Barcelona’s most successful coach. It doesn’t end there, either. Spain’s dominance of international football between 2008 and 2012 served notice that Cruyff’s philosophy has permeated every sector of football in the peninsula. National boss Vicente del Bosque has acknowledged as much.

“Cruyff reinvented the concept of football in this country,” says Miguel Angel Nadal. “Today, Barcelona and Spain are the ultimate modern testimonies to his spell as coach.”

The forefather to arguably the greatest club and national teams ever. That’s quite some legacy to have.

While you're here, why not take advantage of our brilliant new subscribers' offer? Get 5 copies of the world's greatest football magazine for just £5 – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than the cost of a London pint. Cheers!

NOW READ...

QUIZ Can you name every single club Zinedine Zidane scored against?

DOCUMENTARY What REALLY happened to Ronaldo before the 1998 World Cup Final – in his own words

Andrew Murray is a freelance journalist, who regularly contributes to both the FourFourTwo magazine and website. Formerly a senior staff writer at FFT and a fluent Spanish speaker, he has interviewed major names such as Virgil van Dijk, Mohamed Salah, Sergio Aguero and Xavi. He was also named PPA New Consumer Journalist of the Year 2015.