"That season put Liverpool back on the European map" – remembering 2001 with Michael Owen, England's last Ballon d'Or winner

After a season that saw Liverpool win a treble, Michael Owen was crowned Europe's best player. He and Jamie Carragher talk his annus mirabilis, and ponder why he doesn't get the credit he deserves

This interview first appeared in the Autumn 2019 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe to the magazine now and get the first five issues for just a fiver!

JOIN OUR WATCHALONG We'll be watching the whole of Liverpool's 2001 UEFA Cup Final at 3pm on Saturday May 2

Michael Owen has never been one to shout. At his absolute fresh-faced turn-of-the-century peak, there was no swagger, no smug look-at-me celebration – just the sense of someone going about his job to the best of his considerable ability, banging in goals for club and country.

In 2001, Owen was irresistible. He picked up six trophies that year: the FA Cup, League Cup and UEFA Cup treble, plus the Charity Shield and UEFA Super Cup – and then, just three days after turning 22, the Ballon d’Or. He remains the last Englishman to win the award.

The gong came on the back of 31 goals for a Liverpool side desperate to reinstate itself as a force domestically and in Europe. The bigger the game, the better he played. A highly intelligent footballer with brilliant movement, he could time his runs to perfection. He was also, despite his youthful stature, an absolute fiend to get off the ball.

Owen was blessed with a ruthlessness as well; a single-mindedness worthy of Roy Keane. Today, as he sits down to talk with FourFourTwo, the former marksman shrugs when we ask him for his memories of that incredible year. Despite all of the silverware, he rarely stopped to think about what he was accomplishing.

“To me, if you sit back and think about what you’ve just achieved, it’s a weakness,” says Owen. “To be very good, and consistently very good, you need to be greedy, and it has to become an obsession. It’s not so much about the enjoyment of winning something. It’s more about the pain of watching someone else take what should be yours.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

That 2000-01 Liverpool vintage has somehow slipped through the cracks, lost between the white-suited Spice Boys era of the mid-90s and the dramatic triumph of Istanbul. Owen’s old room-mate, Jamie Carragher, reckons the treble-winners were a much better team than the one that saw off Milan in the 2005 Champions League Final.

INTERVIEW Robbie Fowler explains why he’ll never regret THAT celebration against Everton

“It was definitely my favourite season,” the 41-year-old ex-defender tells FFT. “If you win three cup competitions and also finish 3rd in the league, it means you won most of the games you played. And we did. That’s probably the one team I look back at and think, ‘I was playing with all my mates’. Michael was there, Robbie Fowler, Danny Murphy, Steven Gerrard, Didi Hamann, Jamie Redknapp – people I’m still close with now were in that team. Sharing those things together is special.”

That particular Reds outfit wasn’t the easiest on the eye. The path to victory was often built on frustrating the opposition and grinding out results. With Manchester United and Arsenal frequently operating on a completely different level to everyone else, Gerard Houllier’s charges worked within their limitations, making the most of counter-attacking opportunities and a dogged team spirit. “We were a tough side, with a fantastic back four,” recalls Owen. “Sami Hyypia, Stephane Henchoz, Carragher – they were like trojans in every single match they played. We had Hamann and Gerrard too, of course. We had guts, and no one played more games than we did that season. We played every game that was available to us, and that in itself is no mean achievement.”

The first half of that mammoth 63-match campaign had been fairly humdrum, with little to suggest what was to come. Owen, unable to help England out of their Euro 2000 group, hit seven goals in his first six league appearances of the season, including a hat-trick against Aston Villa, but then scored only once in his next 13. A seven-month period from October to April brought him two Premier League goals.

Liverpool weren’t pulling up any trees, either, losing to Ipswich and Middlesbrough in December. Then, something began to spark around the turn of the year. A lot of that was down to Owen clicking into gear. “In that season, with Owen, Fowler, Emile Heskey and Jari Litmanen, we possibly had the best set of strikers in the world,” says Carragher. “Michael didn’t really have a great first half of the season, but as soon as he got his form back, it was scary.”

Owen actually didn’t feature in the first of Liverpool’s trophy wins that season: he was an unused substitute as Houllier started Heskey and Fowler in the League Cup final at Cardiff’s Millennium Stadium. They eventually beat second-tier Birmingham in a penalty shootout.

But while Fowler started in Cardiff, he found himself falling down the Anfield pecking order. Houllier clearly preferred the pairing of Heskey and Owen. The Frenchman had been steadily building his team since arriving on Merseyside in July 1998, initially as joint-manager with Roy Evans. Like his countryman Arsene Wenger, Houllier was something of a footballing Anglophile, keen to marry a Gallic eye for detail with classic English strengths of teamwork, resilience and belief.

“He really dragged the club into this new era of how you look after yourself and prepare,” explains Owen. “We were looking at Arsenal and they were mind-blowing. We were thinking, ‘These buggers don’t get injured, they run faster than us, they run longer than us, they’re never resting players – what the hell are they doing?’

“Houllier was the first to introduce those ideas at Anfield. He could never tell Gerrard how to pass a ball, or me how to finish, or Carragher how to defend, but what he was really good at was judging players. Tactically he was very astute. He was good at motivating and getting us working as a unit. He was a very good leader of people.”

After lifting the League Cup, it was full steam ahead on all fronts, with the UEFA Cup proving a particularly potent platform. The club sensed that it was back on the European stage once again, free from the long shadows cast by events at Heysel and subsequent ban from Europe.

“The UEFA Cup was massive back then,” continues Owen. “We played Barcelona, Roma, Porto, Olympiakos – and that’s before we got to the final. It was a really difficult competition to win.”

Owen had scored twice against Fabio Capello’s in-form Roma at the Stadio Olimpico in February. Liverpool’s quarter-final tie against Porto began with a goalless draw in Portugal, but two quick first-half goals at Anfield from Murphy and Owen, heading in a Gerrard corner, gave Liverpool a comfortable lead that they protected without much grief.

Barcelona awaited in the semis, live on the BBC. Incredibly, kick-off for the first leg at the Camp Nou was put back to 8.10pm at the Beeb’s request, to avoid clashing with EastEnders and the revelation of who shot Phil Mitchell. Presumably all of Barcelona wanted to find out, too.

But there was little drama on offer in Catalonia as the Reds defended in numbers to thwart a Barça side featuring Rivaldo, Luis Enrique, Pep Guardiola and Frank de Boer. The return leg brought a famous victory, with 36-year-old Gary McAllister scoring the only goal from the penalty spot following a Patrick Kluivert handball. It was to be Liverpool’s first European final in 16 years. “We could always take big scalps,” smiles Carragher. “That was the great thing about that team – we may not have been the best, but we could beat the best.”

They were also repeating the trick domestically, working their way to the FA Cup final against Arsenal, back at the Millennium Stadium. Owen went into the game in peak form: in his previous two matches, he’d scored three goals against Newcastle, then two against Chelsea.

Liverpool faced a Gunners side above them in the league table, and Wenger’s side dominated for the most part. Arsenal had three shots blocked on the line – one by Henchoz’s hand, which went unnoticed by the match officials – and once Freddie Ljungberg had rounded Sander Westerveld to put Arsenal in front with 18 minutes remaining, time was rapidly running out for the Reds. Nobody was prepared for what happened next – except perhaps one man.

In the 83rd minute, McAllister launched a free-kick into the penalty area, Markus Babbel nodded the ball down and Owen found space in the crowd to fire in the equaliser. He looks back on that moment now with something approaching reverence; that it was meant to be, even when playing rope-a-dope in the blazing Welsh sun.

“Once I scored that first goal, I jogged back to the halfway line and this feeling came over me: I just knew,” he reveals. “It was like the Ali fight when Foreman was smacking him on the ropes and it seemed impossible, but suddenly, one punch and I knew that Arsenal were gone. They were gone. The only question in my mind was, ‘Have I got enough time to score before the final whistle goes?’ It wasn’t ‘if’, it was ‘when’. I’d never had that feeling before, and I’ve never felt it since.”

Was there time for a winner? Barely five minutes later, Owen had his answer. He latched onto a long pass from Patrik Berger, shrugging off Lee Dixon, before one touch took him away from Tony Adams. On his weaker foot, Owen coolly dispatched a shot into the small goal-bound gap just beyond David Seaman’s outstretched left hand. Michael Owen had won the FA Cup. The forward-flip goal celebration; the screaming, wide-eyed delight; the mayhem in the stands – it all belonged to him.

“It was such a magical day,” he says. “It’s funny: good things happen and you get caught up in the joy of winning for your team-mates and fans. There’s nothing bad about it when you have a day like that.”

Days were becoming a precious commodity at Liverpool. They had only three of them between the FA Cup showpiece in Cardiff and their third final of the campaign, against Alaves in the UEFA Cup. The club from Vitoria-Gasteiz, capital city of the Basque Country, were the big surprise package of the season: they had triumphed 2-0 at the San Siro against an Inter team boasting Christian Vieri and Clarence Seedorf, before shellacking Kaiserslautern 9-2 on aggregate in the semi-finals.

Although Liverpool’s players were now feeling the strains of a long season, they were quickly 2-0 up in Dortmund thanks to Babbel and Gerrard. Alaves pulled a goal back, but Owen tumbled in the box and McAllister converted the penalty. Houllier’s side led 3-1 at the interval.

“I always remember coming into the dressing room, looking around and almost giggling,” Owen admits to FFT. “Some of us were thinking, ‘How good is this? It’s almost a gimme’. You’re expecting the final to be hard, and at half-time I was thinking that they were so easy to beat. Never, ever have I been so wrong. We almost blew it.”

Six minutes into the second half, the score was 3-3. Liverpool’s solid defence was suddenly a shambles. Fowler put them back in front, only for Jordi Cruyff to glance home another Alaves equaliser in the final minute of normal time. “On the way to the final, everyone was saying we were boring – lots of 0-0s and 1-0s – and then it all just went mad in the final!” recalls Carragher with a laugh.

In the end, Liverpool and Owen were able to complete their treble. Alaves had two men sent off in extra time, then Delfi Geli’s own goal gave the Reds a dramatic 5-4 win via the short-lived golden goal rule. It was the club’s first European trophy since Rome in 1984.

“It was where the club needed to be,” explains Owen. “It was such a buzz. The fans were amazing – it felt like we’d taken a million of them to Dortmund.” It was also an important moment for Houllier. “He was desperate to win the UEFA Cup, to put us back on the European map,” adds Owen. “He understood the club’s history and values.”

After two knackering cup finals, there was still a final Premier League match to play in May. Win at Charlton, and Liverpool would be in the Champions League for the first time, back in Europe’s elite competition for the first time since that fateful night at Heysel.

Three days after the UEFA Cup final, Liverpool emerged 4-0 victors at The Valley. Owen set up Murphy to net the third, and scored the fourth himself. The Reds had come 3rd in the table, 11 points off champions Manchester United but down from 24 the previous campaign. “We’d won all those trophies that season and went away that summer proud as punch,” says Owen. “We just needed one or two more players to get a bit better. We wanted to win the league with Liverpool so much. Me and Carra used to speak about it all the time. The desire within us was almost unbearable.”

Owen had the same desire to achieve something with England. With the summer over, and the 2001-02 season only one month old, the national team travelled to Munich to take on Germany in a World Cup qualifier. Trailing to a sixth-minute Carsten Jancker goal, Sven-Goran Eriksson’s men were soon back on level terms, with Owen finding the empty net after Nick Barmby had beaten Oliver Kahn to a high ball. Gerrard put England in front and then Owen ran riot, lashing a strike past a flat-footed Kahn before charging clear to wrap up his hat-trick. It confirmed the 21-year-old as Europe’s most dangerous marksman.

In December came recognition of that fact, as Owen was named the winner of the 2001 Ballon d’Or. He received a total of 176 votes from a panel of sports journalists across UEFA’s member countries. Raul was second with 140 votes, Kahn third with 114 and David Beckham fourth with 102. Francesco Totti, Luis Figo, Rivaldo, Andriy Shevchenko, Thierry Henry and Zinedine Zidane filled out the top 10, but none of them received even a third of Owen’s total votes.

Owen may not have been able to call himself the best player in the world – only in 2007 did the Ballon d’Or become a global award – but he could officially proclaim himself the best player in Europe. He was only the fourth Englishman to receive the honour and the first since Kevin Keegan, a back-to-back winner with Hamburg in 1978 and ’79.

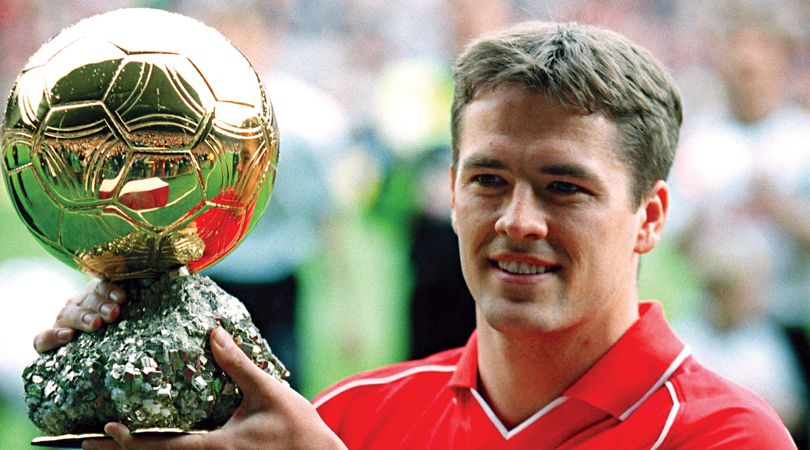

Back in 2001, however, there was very little fanfare about Owen’s prestigious achievement. In England, the cult of the individual had yet to take hold. Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo had yet to emerge. Owen wasn’t even presented with the award at Anfield until April, on the pitch a few minutes before a run-of-the-mill 2-0 win over Derby. Owen scored twice that day, but that was as far as the celebrations went. No gala ceremony. No garish designer tux.

“I believe I don’t get the sort of credit that other people would get for winning the Ballon d’Or,” Owen admits today. “It’s never been that important in our country. When I was in Spain, they said I was a hero for winning it. I’m immensely proud of winning it. I look down the list of names, and I still have it saved on my phone – a photo of the points system and who was second, third, fourth and the rest of it.

“You look at that list and it’s awe-inspiring. That’s all I ever wanted as a kid. I didn’t just want to be a footballer; I wanted to be the best footballer. Winning it feels better now than it did when I was playing. You’re 22 – it’s just another trophy, and now I’ve got to win it again.”

He never did, of course. Injuries, bad luck and Liverpool’s below-par signings didn’t help, as finishing runners-up to Arsenal in 2001-02 was followed by a slide down the table. “We brought in El Hadji Diouf, Salif Diao and Bruno Cheyrou – guys who were expected to propel us, and it just went totally the opposite way,” says Carragher.

Owen and his team-mates struggled to push on from that cup treble of 2000-01 and Houllier eventually departed in 2004, having appeared to run out of ideas. When the chance of a fresh start presented itself to Owen that summer – and at Real Madrid, no less – the 24-year-old was ready to listen.

“The last thing I thought was that I was going to leave Liverpool,” says Owen. “We were on a pre-season tour in America and my agent phoned me while I was in my room with Carragher, who got wind of what we were talking about. I put down the phone and he said, ‘Pffft, don’t go. They’ve got Raul, Ronaldo and Fernando Morientes – you won’t get a game!’ I was 50-50, but I just had this overriding feeling towards it – and I’m blaming Ian Rush, actually! I thought, ‘If I do go, then I’ve already played for Liverpool for a long time and, hopefully, I could always come back, so just go and sample it – the Galacticos; that white kit, where everyone prances out like an angel; that amazing stadium; a different culture’.

“Eventually I agreed. But do you know when you sign something and think there’s no going back? When you think, ‘Oh my God, what have I done?’ I remember crying my eyes out as I went off to the airport, thinking, ‘What am I leaving behind?’”

Owen stops short of using the word ‘regret’, but leaving Liverpool still weighs heavily on him – as does the rather mixed opinions of some on the Anfield terraces towards their former player. His fine international career possibly didn’t help, never quite shaking the sense that he was England’s Michael Owen rather than Liverpool’s Michael Owen. Nor did that squeaky-clean image, with all of the rough edges smoothed out by PRs and agents.

John Gibbons, of Liverpool fan site and podcast The Anfield Wrap, thinks that it’s probably down to sheer numbers – that, and signing for Manchester United in 2009.

“We’ve always been spoilt for strikers,” says Gibbons. “We’ve found it a lot more difficult to find a decent left-back over the past 20 years than a centre-forward. That allows people to discard Michael Owen too easily. Robbie Fowler was more loved, but Owen was brilliant for Liverpool. He would always put so much into it when he was on the pitch. You could tell that he was desperate to win.

“I can understand why he gets so frustrated, because he probably sees players spoken of a lot more fondly when they didn’t put in half the work he did. A lot of it is about what happened afterwards. Going to Real Madrid didn’t go down very well, then when he came back to England and joined Newcastle, it was a surprise. But it was signing for Manchester United that really severed all ties.”

Carragher believes his former room-mate’s heroics of 2001 should place him alongside the Anfield greats; that he should get more love from the club’s fanbase. “I think in time that will come,” he suggests.

Virgil van Dijk has hopes of getting his own hands on the trophy at some point during the next couple of months. But unless or until the Dutch defender does, then for all of their legends, for all of the club’s European glory, only one player has ever bagged the Ballon d’Or while playing for Liverpool. Michael Owen.

While you're here, why not take advantage of our brilliant new subscribers' offer? Get 5 copies of the world's greatest football magazine for just £5 – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than the cost of a London pint. Cheers!

READ MORE...

NIKE Write The Future: How one of football's most iconic adverts ever was made

CORONAVIRUS What would each Premier League season since 2000 have looked like if it ended after 29 games?

ANALYSIS It may sound ridiculous, but there's reason to believe the age of £100m transfers is over

Matt Barker is a freelance journalist and regular feature contributor to FourFourTwo magazine. He specialises in Serie A and Italian football, has interviewed players including Michael Owen and Gianluigi Buffon, as well as covering stories such as Silvio Berlusconi's purchase of AC Milan, and Ronaldo's injury-plagued time at Inter Milan at the turn of the century.

'My surname was a handicap, no doubt. I’d get told, ‘If you wanted to avoid all of the attention, just don’t play football’. But I wanted to because I loved it!': Diego Maradona Jr. achieved great success despite his name proving a hinderance in the sport

‘The pure simplicity of the way Slot has managed the squad is probably the biggest thing I could say about him. It’s not broken, so let’s get on with it’: Liverpool legend full of admiration for Jurgen Klopp's successor at Anfield