Why Arsene Wenger's legacy will forever endure in Africa

Wenger's legacy may be framed by his achievements at Arsenal, but his work also helped change the perceptions of African football across Europe

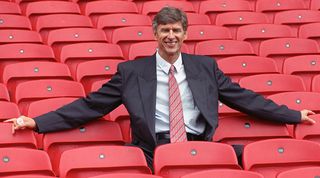

The eulogies for Arsene Wenger have been fulsome in their praise since it was announced that the Frenchman would be leaving Arsenal after almost 22 years in charge this summer.

From his encouragement of healthy lifestyles that were alien to the laddish booze culture of mid-90s English football, to fashioning teams that played aesthetically pleasing football, Wenger has been rightfully hailed for his immeasurable impact across the channel.

But Wenger’s influence on football stretches beyond Europe: he also changed perceptions about African footballers at a time when prevalent attitudes made it unfashionable to sign them.

“He was a father figure”

Wenger’s dalliance with African football and its players began long before his 1996 arrival at Arsenal; during his Monaco days in fact, when he nurtured George Weah from an aspiring-but-callow youth to the polished star who eventually made history as the first non-European winner of the Ballon d'Or (which had been expanded to allow such a thing that year).

Weah was but a virtually unknown 22-year-old when Wenger took a punt on him for £12,000 from Cameroonian side Tonnerre Yaoundé in 1988, after a recommendation from then-Cameroon manager and compatriot Claude Le Roy.

That same player is now Liberia president, and still talks in glowing terms of the man who steered his career in the right path both off and on the pitch when they first met in 1988. Indeed, he even invited Wenger to his inauguration in January.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“He [Wenger] was a father figure and regarded me as his son,” Weah told FIFA.com last November. “This was a man, when racism was at its peak, who showed me love. He wanted me to be on the pitch for him every day.

“Every time I went on the pitch, playing for him, I wanted him to know the ways I could pay him back. I could break my knee, my face, my hand for him – just to win a game.”

Post-Weah, Wenger didn't stop finding and nurturing African talent after his spell at Monaco ended in the sack. He was merely the start: later, Christopher Wreh, the Liberian striker and actual cousin of Weah, became the first African to feature under Wenger at Arsenal when he joined in 1997. (Wenger had also signed him as a 14-year-old at Monaco.)

While there were none when Wenger arrived, Wreh was the first of 16 Africans from 10 different countries to play for the club during his time in charge. Although Wreh’s spell at Arsenal was hardly a roaring success – best remembered for his FA Cup semi-final winner against Wolves in 1998 – Wenger’s next signing from Africa certainly was.

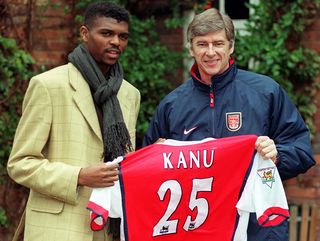

By all indications, Nwankwo Kanu was destined for a career at the elite level before signing for Arsenal in 1999. In 1995, he won the Champions League with Ajax and a year later captained Nigeria's U23 side to Olympic gold in Atlanta. A move to Inter Milan followed after the Olympics, where he was diagnosed with a serious heart condition. Surgery saved his life and career, but he found opportunities few and far between in an Inter side that had recruited Ronaldo from Barcelona.

Here, Wenger saw an opportunity to sign a talented footballer on the cheap – and it worked spectacularly well for both parties. Kanu won numerous individual and team honours at Arsenal and has credited Wenger’s influence on his career.

“I can say that playing under Arsene was one of the best moments of my career,” he told KweséESPN. “He was like a father and the team was like family. That's how we became The Invincibles.”

There's that word again: father.

A visionary approach

Wenger’s work discovering emerging African youngsters continued. Lauren (converted from midfield to right-back by the Frenchman), Kolo Toure (from midfield to centre-back), Emmanuel Eboue, Emmanuel Adebayor and Alex Song all grew into global superstars in their own right under Wenger’s watchful eye. Yaya Toure probably would have done the same had passport issues not hampered a transfer in 2003.

His brother Kolo, perhaps more than anyone else, embodies Wenger’s passion for development with young footballers. He was signed for £150,000 from ASEC Mimosas in his native Ivory Coast after impressing on trial, and Wenger was keen to stress that his new acquisition was still a long way away from first-team football.

“We think he has the basic potential to become a very good player,” Wenger said of Toure in 2002. “He won’t feature in the first-team squad immediately because he’ll need at least three to four months’ work.”

Not only was Wenger quick to spot the talent Toure had, but wise enough to realise that he needed time and patience before being put in the firing line. Without such an attitude, it's difficult to see how the player's career would have developed so successfully.

“I would never say a bad word about Mr. Wenger,” said Toure, then of Manchester City, in 2011. “He is somebody that makes players better. I came from nowhere. I was in Africa and nobody believed in me. I'd been at a lot of clubs that didn't take me. This guy made me what I am now.”

Diamond in the rough

A quick word, too, for Wenger’s influence on Adebayor. Despite the sour ending, there should be no denying that the Togolese owes a lot to his former manager's unwavering belief.

Coming off the back of a four-goal season with Monaco, Adebayor, at 21, was nowhere near the deadly finisher he became for a few years. A combination of Thierry Henry’s departure, Robin van Persie’s injury woes and Adebayor’s own hard work helped him become Arsenal’s leading man – particularly in the 2007/08 season, when he netted 24 Premier League goals.

Wenger’s guiding principles were that talent could be found anywhere, and it was better to mould impressionable youngsters rather than buying expensive recruits.

He also emphasised that African players were just as skilful as their European counterparts, banishing the idea that they were only useful in positions that required their physicality - as prevailing stereotypes dictated.

“African players had a massive impact on my career because I always managed them right from the moment I started in the top league in France,” Wenger said in 2016.

“I had African players at Monaco and I liked the fact that they were creative, and they are usually attacking players with imagination. They have pace and power, and they usually combine strength and agility well. That’s very difficult to find.

“Africans are hugely passionate people and there is a big passion in Africa for the game. They are happy on the football pitch and that’s something which has been fantastic for us.

“Kanu had a massive impact here, Kolo Toure too. I had George Weah too… so all these players had a massive impact.”

Wenger’s faith in African footballers translated to a massive explosion of support for Arsenal on the continent, particularly in Nigeria where a generation of fans blossomed thanks to Kanu’s arrival. It remains an enduring legacy to this day.

As the world became increasingly smaller and scouting networks grew bigger, Wenger eventually lost his edge on the African market. But there is no denying his enormous impact on the careers of many young footballers from the continent, at a time when racial perceptions and the inconvenient timing of the Africa Cup of Nations were roadblocks to their progress.

As Wenger departs to well-deserved adulation in Europe, he also leaves behind a legacy of inspiring belief that's far more wide-reaching.