Yugoslavia at Euro 92: how the Balkan Wars meant the end of an era for the best team never to win the Euros

Prosinecki, Suker, Mijatovic & Co had been fearsome Euro 92 contenders, but civil war in the Balkans meant Yugoslavia were banned before they had the chance to prove it. Many thousands of lives were lost, along with a footballing dynasty

This feature first appeared in the Summer 2021 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe now!

Additional reporting: Sasa Ibrulj, Nebojsa Markovic

Stevan Stojanovic needs no reminder for the date of Yugoslavia’s greatest footballing triumph. “May 29, 1991,” he states, speaking to FourFourTwo from Belgrade. “For the past 30 years, people here haven’t stopped talking to me about it.”

Stojanovic ended that evening as Red Star Belgrade’s goalkeeping hero in the European Cup final, after they defeated Marseille 5-3 on penalties at the Stadio San Nicola in Bari. As captain, he became the only man ever to lift the trophy for a Yugoslav club.

“Velibor Vasovic lifted it as captain of Ajax [in 1971] but this was different,” he explains, the emotions flooding back. “We came from our country, from our streets. That night in the hotel, a man walked up to me. I never found out who he was, but he said, ‘You have no idea what you’ve just done, what kind of achievement this is.’ I was young and wasn’t really thinking about things like that. But that old man was right. As time passed, we all realised what we did. That was the greatest success of Yugoslav football.”

Such was the talent in Yugoslavia during that period, more success surely would have followed. Four years earlier, Zvonimir Boban, Robert Prosinecki, Davor Suker and Predrag Mijatovic had helped the nation’s under-20s to become world champions. When Red Star won the European Cup in 1991, Yugoslavia’s senior team were already well on course to qualify for Euro 92, at eventual winners Denmark’s expense.

But in the space of 368 days, everything collapsed. By May 31, 1992, Yugoslavia had become engulfed by war, and the national team had been kicked out of the Euros. Their dreams of more footballing glory were over.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

There may be trouble ahead

He didn’t realise it at the time, but sweeper Faruk Hadzibegic would have the very last kick of a football for the unified Yugoslavia at a major tournament.

At Italia 90, the Plavi (Blues) faced reigning champions Argentina in the quarter-finals, clinging on for a penalty shootout after Refik Sabanadzovic’s 31st-minute red card. Five men bravely stepped up to take spot-kicks at Florence’s Stadio Comunale: Dragan Stojkovic of Serbia, Prosinecki of Croatia, Dejan Savicevic and Dragoljub Brnovic of Montenegro, and Hadzibegic of Bosnia. After misses from the great Diego Maradona and midfielder Pedro Troglio, victory seemed within Yugoslavia’s grasp. Then both Brnovic and Hadzibegic saw their efforts repelled by Sergio Goycochea.

“Losing to Argentina broke our hearts – we were a kick of a ball away from a World Cup semi-final,” Hadzibegic tells FFT. “We had an extremely talented side, and everything was possible. The generation that won the U20 World Cup was outstanding, and they were just starting to have a bigger impact in the late ’80s and early ’90s, led by Ivica Osim, a fantastic manager. We had one of the best teams in the world.”

Hadzibegic never thought it would be the unified Yugoslavia’s final tournament outing, though. “No, there was no reason,” he says. “Three months later, I was the captain when we beat Northern Ireland 2-0 at Windsor Park with Prosinecki, Savicevic, Stojkovic and Darko Pancev. There was also the likes of Mijatovic, Boban, Suker, Robert Jarni, Vladimir Jugovic, Slavisa Jokanovic, Miroslav Djukic and Meho Kodro. Incredible talents. We were looking forward to the 1994 World Cup, confident we could win things.”

After beginning qualifying for Euro 92 with victory in Belfast, Yugoslavia thrashed Austria 4-1 and then beat Denmark to seize control of their qualifying group. “We beat them 2-0 in Copenhagen,” recalls Mehmed Bazdarevic, one of the goalscorers. “Four players who played that day were from Croatia, four of us were from Bosnia, then there was Predrag Spasic from Serbia, Pancev from Macedonia, and Srecko Katanec from Slovenia. Although Denmark were a great side, we were much better than them.”

There were, however, already signs of the strife ahead. A month before the 1990 World Cup, Red Star travelled to Dinamo Zagreb for a Yugoslav League encounter, just as political tensions were starting to boil over.

Nationalism had slowly been suppressed in Yugoslavia during the 27-year reign of Josip Broz Tito, but when the president died in May 1980, things escalated. Serbian nationalist Slobodan Milosevic had risen to power in Belgrade by the time Croatia held their first multi-party elections in more than 50 years, in early May 1990. Croatian nationalist Franjo Tudjman emerged victorious, lighting the fuse for one of the most explosive football matches in history.

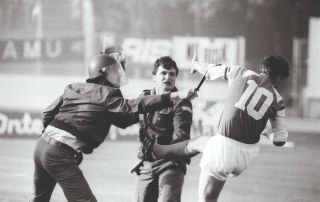

In fact, the match never actually started. Violence erupted before kick-off between Dinamo’s Bad Blue Boys ultras and the Delije, Red Star’s hardcore fans, led by the notorious mobster Arkan. Responding to stones thrown by the Bad Blue Boys, the Delije lobbed seats, chanting “Zagreb is Serbian” and “we’ll kill Tudjman”. Home fans then invaded the pitch, sparking a full-scale riot. Amid the mayhem, Boban aimed a flying kick at a police officer who Dinamo’s young star felt had mistreated one of his club’s supporters.

“Here I was, a public figure prepared to risk his life, career,” Boban later recalled, “all for one ideal, one cause; the Croatian cause.” Some have labelled it ‘the kick that started a war’, claiming the riot played its part in the destructive events that followed.

“That game was sort of a beginning of the end for Yugoslavia,” says Red Star keeper Stojanovic. “We were well received in Zagreb before the game – we were in the hotel and didn’t see anything odd happen. Rocks were thrown at us during the warm-up, then our coach told us, ‘Let’s go to the dressing room.’ Right as we were going there, the Dinamo fans came from the north stand, while Red Star fans were in the south stand.

“That was really bad to see, but we left the pitch just in time. We went to the VIP box and waited for the police to clear the roads for us to go back to Belgrade. It was a huge surprise to not even play the match. There was a big rivalry with Dinamo, but nothing like that had happened before. It looked as if somebody used sport for their cause.”

The Yugoslav FA suspended Boban for six months, ruling him out of the World Cup. In their final friendly before the tournament, Yugoslavia played the Netherlands in Zagreb and were jeered by a pro-Croat crowd.

“That was a surreal experience,” continues Hadzibegic. “I remember the shock as they booed our anthem. Nine months earlier, we defeated Scotland 3-1 in the same stadium with more than 40,000 people supporting us fiercely. I reacted instinctively, clapped my hands and shouted, ‘Let’s go, us 11 against 20,000 of them,’ and that was caught by TV. We were preparing for the World Cup and our own fans were booing us.”

Hadzibegic denies the rise of nationalism across Yugoslavia caused friction within the squad. “I never felt any tensions between players of different nationalities,” he insists. “I was born in Sarajevo, but I always felt like a proud Yugoslav and I couldn’t say that any of my team-mates felt different.

“Sometimes we’d joke about stereotypes of people from different Yugoslav republics, but it was just dressing room banter which happens with every team, with every group of friends. Nothing ever changed inside the team. We were aware of everything that was happening around us, but we all ignored it.”

The last hurrah

The events off the field didn’t derail Red Star Belgrade in the 1990/91 season, either. The Croatian War of Independence had begun just weeks before Croat midfielder Prosinecki and Serbian forward Dragisa Binic combined for one of the finest team goals in European Cup history, netted by Macedonian Pancev, in a semi-final first-leg victory over Bayern Munich. They completed the job in front of an 80,000 Belgrade crowd, thanks to a late own goal from Klaus Augenthaler.

“That was the last game of such magnitude played in the old Yugoslavia,” says Stojanovic. “When Bayern scored that own goal at the end, it was pandemonium in the Marakana.”

The final against Chris Waddle’s Marseille went to a shootout after a dismal 0-0 draw.

“We’d played eight matches before that in a very attractive style, scoring goals, playing great football,” explains Stojanovic (pictured receiving the trophy below). “But our coaching staff had watched Marseille closely. Our boss Ljupko Petrovic said, ‘Do you want to play the final the way I think we should and win, or do you want to play the way we have so far, but then I can’t promise you the cup?’ Of course, we all wanted that trophy.

“Petrovic told us we were not supposed to score. He said, ‘It ends 0-0, Stojanovic will save a penalty in the shootout and we are the champions of Europe’. And that’s exactly what happened – incredible. You can even ask Ljupko himself!”

Red Star also won the Yugoslav domestic title for a second successive season – the final campaign before the league started to disintegrate. Earlier that season, a match between Hajduk Split and Partizan Belgrade had been abandoned when Croatian home fans chased the Partizan team off the pitch, then set fire to a Yugoslav flag.

When Red Star returned to Zagreb to face Dinamo in the final weeks of the campaign, a year on from the Maksimir Stadium riot, the hosts came from behind to triumph 3-2 in front of the watching Tudjman. “We went 2-0 up, but Dinamo were given a scandalous penalty,” Red Star coach Petrovic later said. “At half-time I protested vehemently with the referee, and from what he told me it was apparent between the lines that we had to lose the game for political reasons. Tudjman was sitting in the stands and he didn’t want a Serbian team celebrating in front of him in Zagreb, at a moment when he was creating an independent state.”

Days before that match, Croats Prosinecki, Boban and Suker had all scored as Yugoslavia battered the Faroe Islands 7-0 in a Euro 92 qualifier. They would never play for the side again. Croatian players quit the Yugoslavia team that summer, and later helped their independent country to finish third at the 1998 World Cup.

“There was talk about the Croatian players leaving for some time, but when they pulled out it was a hard blow,” says Bazdarevic. “We didn’t see it as farewell, though – we thought they’d come back in a couple of months once everything settled down.”

War in Croatia continued for another four years, despite a declaration of independence in June 1991. It claimed an estimated 20,000 lives and displaced well over half a million more from their homes. Slovenia made the same declaration the same day, and Croatian and Slovenian clubs subsequently withdrew from the Yugoslav League.

Red Star suffered, too, as their team began to break up. Prosinecki signed for Real Madrid, Binic moved to Slavia Prague and Stojanovic joined Antwerp. “That was sad – it wasn’t the club’s decision that made the team fall apart, but politics,” he says. “A year before we won the European Cup, I had an offer from Real Oviedo but Red Star told me to stay for one more year. I stayed, we won the European Cup, then I got an offer from Antwerp. I told the club and they said, ‘This country is falling apart, you should go.’”

Red Star saw off Colo-Colo 3-0 to win the Intercontinental Cup in Tokyo, but lost 1-0 to Manchester United in the UEFA Super Cup at Old Trafford. The title was usually contested over two legs, but it was deemed unsafe to play in Belgrade. Red Star’s European home games were moved to Hungary and Bulgaria, but they still came close to reaching another final, aided by Pancev and Savicevic, who had shared second place in the 1991 Ballon d’Or.

The pair were still part of the Yugoslavia squad too, as the Plavi qualified for Euro 92, topping Group 4 to eliminate Denmark. But Pancev’s future would soon be thrown into doubt, as Macedonia declared independence in September 1991.

Banned and disbanded

In March 1992, politics would overshadow football once more, as Red Star met Partizan in a domestic league match. Normally bitter Belgrade rivals, ultras of both clubs united in applause when a Serbian paramilitary group known as the Tigers began holding up road signs in the stand – ‘20 miles to Vukovar’,

‘10 miles to Vukovar’, ‘Welcome to Vukovar’. They were trophies of all the towns they had taken during the war in Croatia. The Tigers were led by Arkan, who had recruited heavily from Red Star’s Delije. He was later indicted for war crimes.

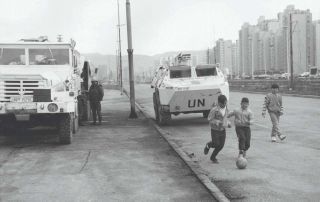

The same month, events in Yugoslavia took another dark turn. Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence, and the Bosnian War soon broke out. Serb forces commenced the Siege of Sarajevo, which would last for nearly four years, and carried out a massacre in the city of Bijeljina.

Just 19 days before Yugoslavia were due to face England in their opening Euro 92 game, their Sarajevo-born manager resigned. Osim stated, “My country doesn’t deserve to play in the European Championship.”

The squad’s Bosnian players departed, too. “It was a very difficult thing to do, but it was inevitable,” concedes Hadzibegic, the team’s captain until then. “As soon as the first armed conflicts started, I spoke to the manager and a couple of officials, and we agreed that it would be almost impossible for us to play at the tournament.

“I didn’t think about the consequences for my football career. There was war starting in our country – people were dying, fleeing their homes, and women were being raped. We all hoped that this thing would end in a matter of weeks or months. We couldn’t comprehend that the world would allow a war to happen in the middle of Europe.”

It proved a painful end to the 34-year-old’s international career. Pancev also pulled out, as Yugoslavia played a warm-up match in Italy against Fiorentina shortly before flying to Sweden for the Euros.

They wouldn’t stay for long. When Serbian general Ratko Mladic ordered more shelling of Sarajevo, the UN acted by placing sanctions on Yugoslavia. FIFA and UEFA responded by banning the national team from international football, on May 31. They would be replaced at the Euros by Denmark, who went on to win the whole thing.

“It felt like everything had been taken away from me – everything I worked for, everything I hoped for,” Bazdarevic remembers of that awful spell. “I was playing great football, and maybe would have signed for Barcelona after that tournament. Who knows? It felt worse when Denmark won it, because I knew we should have been there in their place. It was dramatic for all of us, but nothing compared with what was happening at home. People were getting killed.”

Banned from both the 1994 World Cup and Euro 96, Yugoslavia wouldn’t make a major finals until 1998, by which time it consisted of only Serbia and Montenegro. All Yugoslav League clubs were removed from European competitions until 1995. Red Star’s remaining heroes headed to Italy in the summer of ’92 – Pancev to Inter, Jugovic to Sampdoria, Sinisa Mihajlovic to Roma and Savicevic to Milan, where he starred two years later in winning another European Cup. Mijatovic left Partizan for Valencia in 1993, and later conjured up Real Madrid’s winner in the 1998 Champions League Final against Juventus.

Croatia would finish third at France 98, with Suker (pictured above) picking up the Golden Boot.

In June 1992, the last thing any of that Yugoslav generation wanted to do was watch the tournament they had just missed out on.

“More important things were on my mind,” says Hadzibegic. “I can tell you one thing: if we’d all stayed together, if we’d played that tournament in normal circumstances, if we’d had a chance to compete, I’m sure we would have won it. We would have won Euro 92.”

NOW READ

RETRO Remembering Red Star Belgrade’s European Cup winners, 29 years on from their greatest victory

EURO 2020 Golden Boot: 8 contenders in the race for top scorer

QUIZ Can you give 50 correct answers in The Big Champions League Quiz?

Chris joined FourFourTwo in 2015 and has reported from 20 countries, in places as varied as Jerusalem and the Arctic Circle. He's interviewed Pele, Zlatan and Santa Claus (it's a long story), as well as covering the World Cup, Euro 2020 and the Clasico. He previously spent 10 years as a newspaper journalist, and completed the 92 in 2017.